Submitted by ICConline on

Eighty years ago, one of the most important events of the 20th century, the Spanish Civil War, came to an end. This major conflict was at the heart of the world situation in the 1930s. It had been at the centre of international political attention for several years. It would provide a decisive test for all political tendencies claiming to be proletarian and revolutionary. For example, it was in Spain that Stalinism would play a part, for the first time outside the USSR, as the executioner of the proletariat. Likewise, it would be around the Spanish question that a decantation would take place within the currents that had fought against the degeneration and betrayal of the communist parties in the 1920s, a decantation dividing them into those who would maintain an internationalist position during the Second World War and those who ended up participating in it, such as the Trotskyist movement. Even today, positions on the events of 1936-1939 in Spain are central in the propaganda of the currents that claim to support proletarian revolution. This is especially the case for the different tendencies of anarchism and Trotskyism which, despite their differences, both agree that there was a "revolution" in Spain in 1936. A revolution that, according to the anarchists, went much further than that of 1917 in Russia because of the constitution of the "collectives" promoted by the CNT, the anarcho-syndicalist trade union, an analysis rejected at the time by various currents of the Communist Left, by the Italian Left and also by the German-Dutch Left.

The first question for us to answer therefore is: was there a revolution in Spain in 1936?

What is a revolution?

Before answering, we need to agree on what exactly is meant by "revolution". It is a particularly overused term since it is claimed in France for example by both by the extreme left (Mélenchon with his "Citizen Revolution") and by the extreme right (the "National Revolution" of the Front Nationale). President Macron himself entitled the book setting down his political programme, "Revolution".

In fact, beyond all the fanciful interpretations, the term "Revolution" has historically expressed and entailed a violent change of political regime where the balance of power between social classes is overturned in favour of those representing progressive change in society. This was the case with the English Revolution of the 1640s and the French Revolution of 1789, both of which attacked the political power of the aristocracy in the interests of the bourgeoisie.

Throughout the 19th century, the political advances of the bourgeoisie at the expense of the nobility represented progress for society. And this is because at that time the capitalist system was experiencing growing prosperity and setting out to conquer the world. However, this situation would change radically in the 20th century. The bourgeois powers had finished sharing out the world between them. Any new conquests, whether colonial or commercial, would involve challenging the claims of a rival power. This gave rise to the increase in militarism and the outbreak of imperialist tensions that led to the First World War. This was a sign that capitalism had become a decadent and obsolete system. The bourgeois revolutions were no longer relevant. The only revolution on the agenda was the one to overthrow the capitalist system and establish a new society free of exploitation and war, i.e. communism. The only subject of this revolution is the class of wage earners that produces most of the world's social wealth, the proletariat.

There are fundamental differences between bourgeois revolutions and the proletarian revolution. A bourgeois revolution, i.e. the seizure of political power by the representatives of a country's bourgeois class, is the outcome to a whole historical period during which the bourgeoisie has acquired a decisive influence in the economic sphere through the development of trade and techniques of production. The political revolution, the abolition of the privileges of the nobility, constitutes an important (although not indispensable) step in the growing control by the bourgeoisie over society, which enables it to achieve and accelerate this process of control.

The proletarian revolution does not in any sense emerge at the end of a process of economic transformation of society, but on the contrary is active from the very start. The bourgeoisie had been able to establish its own economic “islands” within feudal society, with trade in the towns and other commercial networks, 'islands' that gradually would grow and be consolidated. It's nothing like this for the proletariat. There can be no islands of communism in a global economy dominated by capitalism and market forces. This was the dream of the utopian socialists such as Fourier, Saint-Simon and Owen. But, despite all their goodwill and their often profound analyses of the contradictions of capitalism, their dreams clashed with and were shattered by the reality of capitalist society. The fact is that the first stage of the communist revolution consists in the seizure of political power by the proletariat worldwide. It is only through its political power that the revolutionary class will be able to gradually transform the global economy by socialising it, by abolishing private ownership of the means of production along with market relations.

There are two other basic differences between bourgeois revolutions and the proletarian revolution:

- Firstly, while bourgeois revolutions have taken place at different times depending on the economic development of each particular country (there is more than a century between the English and French revolutions), the proletarian revolution must be concluded within the confines of the same historical period. Should it remain isolated within a single country or within a few countries, it would be condemned to defeat. This is what happened to the Russian revolution of 1917.

- Secondly, bourgeois revolutions, even extremely violent ones, still retained most of the state apparatus of feudal society (the army, police, legal system and bureaucracy). In fact, the bourgeois revolutions took charge of modernising and perfecting the existing state apparatus. This was possible and necessary since this type of revolution provided for a process of succession between the two exploiting classes, the nobility and the bourgeoisie, to the helm of society. The proletarian revolution is completely different. In no way can the proletariat, the exploited class at the heart of capitalist society, use the state apparatus designed and organised to guarantee this exploitation, and to suppress the struggles against this exploitation, for its own benefit. The first of the tasks of the proletariat in the course of the revolution will be to arm itself in order to destroy the state apparatus from top to bottom and to set up its own organs of power based on its mass unitary organisations with elected delegates revocable by general assemblies: the workers' councils.

1936: a revolution in Spain?

On July 18, 1936, following a military coup against the Popular Front government, the proletariat took up arms. It was successful in defeating the criminal enterprise led by Franco and his associates inside most major cities. But did it then take advantage of this situation, of its position of strength, to attack the bourgeois state? A bourgeois state which, since the establishment of the Republic in 1931, had already distinguished itself in the bloody repression of the working class, particularly in the Asturias in 1934 where 3,000 were killed. The answer is 'absolutely not!'

For sure the workers' response was initially a class action, preventing the coup from succeeding. But, unfortunately, the workers' energy was quickly channelled and ideologically recuperated behind the state banner by the mystifying force of the Popular Front's "antifascism". Far from attacking and destroying the bourgeois state, as was the case in October 1917 in Russia, the workers were diverted and recruited into defending the republican state. In this tragedy, the anarchist CNT, the most powerful trade union movement, played a leading role in disarming the workers, pushing them to abandon the terrain of the class struggle and capitulate, handing them over, with their hands and feet bound, into the arms of the bourgeois state. Instead of leading an attack on the state aimed at destroying it, as they have always claimed to want to do, the anarchists took charge of some of the ministries, stating, as Federica Montseny, anarchist minister of the republican government did:

"Today, the government, with the power to control the state organs, has ceased to be an instrument of oppression against the working class, just as the state no longer acts as an organism that divides society into classes. Both will oppress the people much less now that members of the CNT are involved in them”. The anarchists, who claim to be the state's "worst enemies", were thus able, using this type of rhetoric, to lead the Spanish workers into a pure and simple defence of the democratic state. The working class was diverted from its own political goals into supporting the "democratic" faction of the bourgeoisie against the "fascist" faction. This reflects the full extent of the political, moral, and historical bankruptcy of anarchism. Where it was politically dominant in the Iberian peninsula, anarchism showed its total inability to defend class politics, to stand up for working class emancipation. The class was simply led to defend the democratic bourgeoisie and the capitalist state. But the bankruptcy of anarchism did not stop there. By pretending it could lead the revolution on the basis of local actions that gave rise to the "collectives" of 1936, it actually rendered a proud service to the bourgeois state;

- on the one hand, it made possible the reorganisation of the Spanish economy in the interest of the war effort of the republican state, i.e. it supported representatives of the democratic bourgeoisie, against the "fascist" faction of the same bourgeoisie;

- on the other hand, it diverted the proletariat away from taking a generalised political action and into taking direct charge of the management of the factories and plants. This also benefitted the State and therefore the bourgeoisie. The workers were recruited into the "collectives" to deal with day-to-day production, into abandoning a global political activity and all concern for the real needs of the working class in favour of managing local enterprises, leaving them with no contacts between them.

While the proletariat was master of the streets in July 1936, in less than one year it was displaced by the coalition of republican political forces. On May 3, 1937, it made one last attempt to challenge this situation. On that day, the "Assault Guards", police units of the Government of the Generalitat of Catalonia - in fact they were tools of the Stalinists who had gained control over them - tried to occupy the Barcelona telephone exchange that was in the hands of the CNT. The most combative part of the proletariat responded to this provocation by taking control of the streets, erecting barricades and going on strike; an almost general strike. The proletariat was fully mobilised and certainly had weapons, but it didn't have a clear perspective. The democratic state had remained intact. It was still on the offensive, contrary to what the anarchists had said, and had in no way given up plans to suppress attempts at resistance by the proletariat. While Franco's troops voluntarily brought an end to the offensive at the Front, the Stalinists and the republican government crushed the very workers who, in July 1936, had defeated the fascist coup d'état. It was at this moment that Federica Montseny, the most prominent anarchist minister, called on the workers to stop fighting and to lay down their arms! So it was a real stab in the back for the working class, a real betrayal and a crushing defeat. This is what the magazine Bilan, publication of the Italian Communist Left, wrote on this occasion: "On July 19, 1936, the proletarians of Barcelona overpowered the attack of Franco's battalions THAT WERE ARMED TO THE TEETH USING THEIR BARE HANDS. On May 4, 1937, these same proletarians, NOW DISARMED, left behind them many more fallen victims on the streets than in July when they had had to repel Franco; and now it was the antifascist government (even including the anarchists, to which the POUM indirectly gave solidarity) that unleashed the scum of the repressive forces against the workers".

In the widescale repression that followed the defeat of the May 1937 uprising, the Stalinists were actively engaged in the work of physically removing any "troublesome individuals". This was what happened, for example, to the Italian anarchist activist, Camilo Berneri, who had had the lucidity and courage to make a damning criticism of the CNT's policy and the action of the anarchist ministers in an "Open Letter to Comrade Federica Montseny".

To claim that what happened in Spain in 1936 was a revolution that was "superior" to the one that took place in Russia in 1917, as the anarchists do, not only totally turns its back on reality, but constitutes a major attack on the consciousness of the proletariat by discarding and rejecting the most precious experiences of the Russian revolution: in particular those of the workers' councils (the Soviets), the destruction of the bourgeois state, the appeals to proletarian internationalism and the fact that this revolution was conceived as the first stage of world revolution and gave an impetus to the constitution of the Communist International. Despite the anarchists’ assertions to the contrary, proletarian internationalism was proven to be quite alien to the majority of the anarchist movement, as we will see later.

The Spanish Civil war, a preparation for the Second World War

The first thing that confirms our view that the Spanish Civil War was only a prelude to the Second World War and not a social revolution, is the very nature of the fighting between different fractions of the bourgeois state, republicans and fascists, and that between nations. The CNT's nationalism led it to call explicitly for the world war to save the "Spanish nation": "Free Spain will do its duty. In the face of this heroic attitude, what will the democracies do? It is to be hoped that the inevitable will not be long in coming. Germany's provocative and blunt attitude is already unbearable. (...) Everyone knows that, ultimately, the democracies will have to intervene with their air squadrons and armies to block the passage of these hordes of fanatics..." (Solidaridad Obrera, CNT newspaper, 6 January 1937, quoted by Proletarian Revolution No. 238, January 1937). The two battling bourgeois factions immediately sought outside support: not only was there a massive military intervention by fascist states that delivered air support and modern army weapons to the Francoists, but the USSR was also involved in the conflict, supplying arms and "military advisors". There was enormous political and media support, all over the world, for one bourgeois camp or the other. By contrast, no great capitalist nation had supported the Russian Revolution in 1917! Quite the opposite: they had all done what they could to isolate it and fought against it militarily, trying to drown it in blood.

One of the most spectacular illustrations of the role of the war in Spain in preparing the ground for the Second World War was the attitude of many anarchist militants towards it. Thus, many of them became involved in the Resistance, i.e. the organisation representing the Anglo-American imperialist camp on French soil that was occupied by Germany. Some even joined the regular French army, notably the Foreign Legion or General Leclerc's Second Armoured Division; this same Leclerc would later be actively involved in the colonial war in Indochina. Thus, the first tanks that entered Paris on 24 August 1944 were driven by Spanish soldiers and sported the portrait of Durruti, an anarchist leader and commander of the famous "Durruti column", who himself died outside Madrid in November 1936.

All those who, while claiming to be part of the proletarian revolution, took up the cause of the Republic, of the "democratic camp", generally did so in the name of the "lesser evil" and against the "fascist danger". The anarchists promoted this democratic ideology in the name of their "anti-authoritarian" principles. According to them, even if they admit that "democracy" is one of the expressions of capital, it still constitutes a "lesser evil" for them compared to fascism because, it is obviously less authoritarian. That's total blindness! Democracy is not a "lesser evil". On the contrary! It is precisely because it is capable of creating more illusions than the fascist or authoritarian regimes, that it constitutes a weapon of choice of the bourgeoisie against the proletariat.

Moreover, democracy is not to be underestimated when it comes to suppressing the working class. It was the "democrats", and even the "Social Democrats", Ebert and Noske, who had Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg murdered, along with thousands of workers, during the German revolution in 1919, bringing to a halt the extension of the world revolution. Where the Second World War is concerned, the atrocities committed by the "fascist camp" are well known and documented, but the contribution of the "democratic camp" cannot be forgotten: it was not Hitler who dropped two atomic bombs on civilian populations, it was the "democrat" Truman, the president of the great "democracy" of the United States.

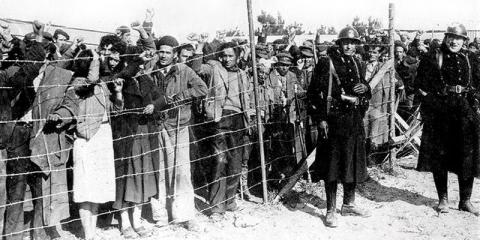

And in looking back at the Spanish Civil War, we should remember the welcome that the French Republic, the champion of "human rights" and "Liberté-Égalité-Fraternité", gave to the 400,000 refugees who fled Spain in the winter of 1939 at the end of the civil war. Most of them were housed in concentration camps like cattle surrounded by barbed wire, under the armed guard of the gendarmes of French democracy.

The proletariat must learn the lessons of the Spanish War:

- Unlike those who want to bury the proletariat and seek to discredit its struggle, those who think that the tradition of the Communist Left is "obsolete" or "old fashioned", that we should free ourselves from the revolutionary past of the proletariat, that Spain was a "superior" revolutionary experience and that finally we should forget the past and "try something different", we affirm that the workers' struggle remains the only way forward for the future of humanity. Therefore it is essential that we defend the working class's legacy and its traditions of struggle, in particular the need for class autonomy in fighting uncompromisingly for its own interests, on its own class terrain, with its own methods of struggle and its own principles.

- A proletarian revolution is not at all the same as the "antifascist" struggle or the events in Spain in the 1930s. Quite the contrary, it has to situate itself on the political terrain of the conscious workers' struggle, based on the political force of the workers' councils. The proletariat must maintain its self-organisation and its political independence from all factions of the bourgeoisie and from all ideologies that are alien to it. This is what the proletariat in Spain was unable to do since, quite the contrary, it bound itself, and therefore surrendered, to the left-wing forces of capital!

- The Spanish Civil War also shows that it is not possible to begin "building a new society" through local initiatives at the economic level, as anarchists choose to believe. Revolutionary class struggle is first and foremost an international political movement and not limited to preliminary economic reforms or measures (even through seemingly very radical "experiments"). The first task of the proletarian revolution, as the Russian Revolution has shown us, must be a political one: the destruction of the bourgeois state and the seizure of power by the working class on an international scale. Without this, it is inevitably doomed to isolation and defeat.

- Finally, democratic ideology is the most dangerous of all those promoted by the class enemy. It is the most pernicious, the one that makes the capitalist wolf look like a protective lamb and "sympathetic" to the workers. Antifascism was therefore the perfect weapon in Spain and elsewhere used by the Popular Fronts to send workers to be massacred in the imperialist war. The State and its "democracy", as a hypocritical and pernicious expression of capital, remains our enemy. The democratic myth is not only a mask of the state and the bourgeoisie to hide its dictatorship, its social domination and exploitation, but also and above all, the most powerful and difficult obstacle for the proletariat to overcome. The events of 1936/37 in Spain amply demonstrate this and it is one of their most important lessons.

ICC, June 2019

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace