Submitted by International Review on

Within the working class, there exists a historical ‘collective memory’. Revolutionary political organizations are an important sign of its existence, but not the only one. Throughout the class, conclusions have been drawn from the years past struggles and of ruling-class onslaughts, often more or less consciously, often in a purely negative form, more in the sense of knowing what not to do than disengaging a precise, clear and positive perspective. The power and depth of the workers’ movement in Poland were in large part the direct fruit of the successive experiences of 1956, 1970 and 1976.

This is why, within the worldwide unity of the proletariat, the different sections of the class are not all identical some have a longer tradition, a greater tradition than others. Old Western Europe regroups the proletariat with the strongest industrial heart (there are 41 million industrial wage-earners in the EEC, as opposed to 30 million in the USA and 20 million in Japan) and the longest historical experience; here the proletarian steel has been tempered by struggles that stretch from 1848 to the Paris Commune and the revolutionary wave at the end of World War I, by the confrontation with the counter-revolution in all its forms - Stalinist, fascist and ‘democratic’ (unionism and parliamentarism) - by hundreds of thousands of strikes of all forms and of sizes1.

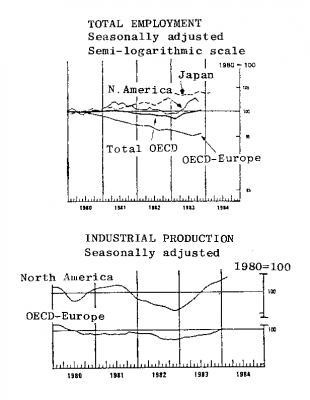

Today, not only are the world proletariat’s major battalions concentrated in Western Europe, this is also the industrialized part of the US bloc where the revolutionary class, in the short- or medium-term, is destined to undergo the most violent economic attack. Western European capital is slowly collapsing, incapable of confronting (either on the world market or its own internal market) the economic competition of its American or Japanese 'partners' - a competition that has become all the more aggressive and merciless since these latter have themselves been plunged into the deepest crisis since the 1930s.

The combination of these subjective and objective conditions are transforming Western Europe into the formidable revolutionary detonator foretold by Marx.

The economic decline of Europe

In the decade from 1963-1973, the economies (GDP) of the EEC states grew by a yearly average of 4.6%. The rate fell to 2% in the decade that followed. At the beginning of the 1980s, it had fallen to zero or less in several countries. At the end of the 1960s, unemployment in the EEC stood at 2.3% of the working population. Today it is over 10% and has reached 17% in countries as different as Spain and the Netherlands. Between 1975 and 1982, the EEC’s ‘market share’ (measured by its share of total exports of manufactured products throughout the OECD) fell from 57% to 53%, while the USA’s remained stationary at 18% and Japan's rose from 13% to 16%.

In the second half of the ‘70s, the West European economy increasingly lost ground before the American and Japanese. This tendency speeded up at the beginning of the 1980s. At the same time, European capital's dependence on the power of its bloc leader - firmly established ever since the Second World War - has increased sharply.

Western Europe’s economic decline within the bloc is partly explained by the characteristics of international relations in decadent, militarized capitalism.

The law of the strongest

The laws that regulate relations between national capitals - even within the same military bloc - are those of the underworld. When the crisis hits, the economic competition by which the capitalist world lives rises to a paroxysm, just as gangsters shoot it out when the loot is rarer and more difficult to get.

In the present period this is expressed on the planetary level by the worsening tensions between the two military blocs. Within each bloc, each nation is under the absolute military control of the dominant power (the ammunition of the Japanese, like the Polish, army is kept at a strict minimum; it is supplied by its bloc leader). But economic antagonisms are none the weaker for all that.

Within the richer western bloc, a certain freedom of competition - much less than official propaganda pretends - makes it possible for economic antagonisms to appear in broad daylight: war is waged with reduced production costs, state export subsidies, protectionist measures and ‘market share’ bargaining, etc. In the poorer Eastern bloc, still more ruined by a gigantic effort of militarization, the economic tensions between national capitals appear less clearly, being more suppressed by military imperatives. (East Germany is proportionately more industrialized than the USSR; it is nonetheless obliged to buy Russian oil at an arbitrarily fixed price which is always higher than that of the world market and is usually obliged to pay in hard (western) currency).

However, with the acceleration of world capitalism’s crisis and decadence, it is the more backward bloc’s way of life that shows the shape of things to come for the better-off. As we said at our Second International Congress (1977), “The United States is going to impose rationing on Europe”. Since the beginning of the 1970s, the West has moved, not towards a greater freedom of trade and economic life, but on the contrary towards a proliferation of protectionist measures and the ever more merciless domination of the US over its rivals. The most recent reports of the GATT, the organization supposed to defend and stimulate free trade between nations, complain endlessly and denounce the suicidal sacrilege of proliferating customs barriers and other measures hindering ‘free trade’ between nations.

As for the USA’s economic relations with its industrialized partners, these are characterized - above all since the so-called oil crisis - by a series of economic maneuvers, whose concrete result boils down to ‘looting’. And the fruits of this plunder are essentially used by the dominant power to finance its military expenditure.

Like the USSR, the United States bears the heaviest military load of its bloc2. Ever since the Nixon presidency, the USA’s bloc-wide military-economic policies have forced its vassals to finance a part of its military strategy.

The violent increases in the price of oil (1974-75, 1979-80) whose production and distribution is largely controlled, directly or indirectly, by the US, have provided:

1) through the flood of dollars that poured into the Middle East from Europe and Japan, the means to finance the ‘Pax Americana’, essentially via Saudi Arabia;

2) through the enormous demand for dollars thus created (since oil is traded in dollars), an over-valuing of the green-back which allowed the US to buy anything, anywhere, at lower cost. This amounts to a forced revaluation of the dollar.

Since the beginning of the ‘80s, the US policy of high interest rates has had an analogous effect. The economic crisis creates a mass of ‘inactive’ capital, in the form of money, which cannot be profitably invested in the productive sector since the latter is constantly diminishing. If it is not to disappear (at least in part) it is forced to find placements in the speculative sector, where it is transformed into fictitious capital. These placements are made where interest rates are highest. US policy is thus sucking in an enormous mass of capital from throughout the world, which must be converted into dollars to be placed. The demand for the dollar grows and its price rises: it is overvalued (some January 1984 estimates put this over-valuation at 40%). Buying cheap (or rather, at the price it imposes), the US can afford the luxury of the biggest balance of payments deficit in its history ... without its currency being devalued; quite the reverse - at least for the moment. At the same time, and with the same impunity, the budget deficit has reached the unprecedented level of $200 billion, ie the equivalent of official defense spending estimates.

As we have pointed out several times in previous issues of this Review, this policy cannot go on forever. This headlong flight is simply laying the groundwork for gigantic financial explosions to come.

Conducting a policy of high real interest rates means being able to repay the borrowed capital with high real revenues. But the economic crisis, which is also devastating the US, deprives it of the real means for paying the interest. As for military production, which alone is undergoing any real development, this destroys rather than creates these means of payment. In reality the US pays these revenues with paper which is, in its turn, reinvested in the USA. At the end of this road, lies the bankruptcy of the world financial system3.

But the USA does not really have any choice and is not leaving any to its ‘allies’ either. The American economy 'supports' the European just as the rope supports a hanged man.

Just as in the rival bloc, and as in the whole of social life under decadent capitalism, economic relationships within the US bloc are increasingly modeled on and subservient to military relationships.

Speaking of relations between Europe and the bloc leader, Helmut Schmidt - an experienced representative of German capital - declared recently that Washington tends to “replace or supplant its political leadership by a strict military command, demanding that its allies obey orders without discussion, and within two days.” (Newsweek, 9.4.84)

********************

In the Eastern bloc, the USSR plunders its vassals directly, under the menace of its military might. In the Western bloc, the United States’ pillage is conducted essentially through the play of the economic mechanisms of the ‘market’ that they dominate militarily. But the result is the same. The bloc leader pays for its military strategy with the tribute of its vassals, whether direct or indirect.

Europe’s increasing lag is largely the result of the capitalist world’s law: the law of the strongest.

The intrinsic weaknesses of the European economy are those of a continent divided into a multitude of nations, competing amongst themselves and incapable of overcoming their divisions, in order to concentrate their forces to resist the economic competition of powers like America and Japan.

The myth of the common market

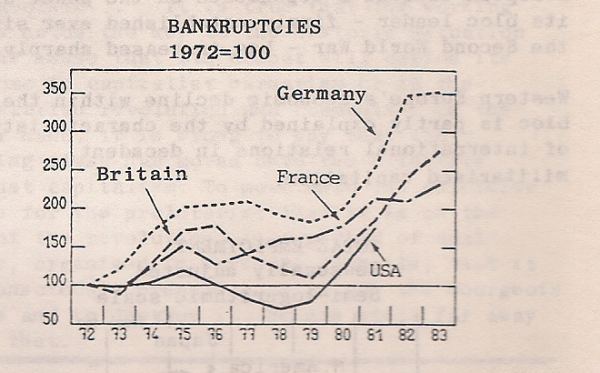

One of the most classic signs of economic crisis is the proliferation of company bankruptcies. For several years these have spread with growing rapidity, like an epidemic, throughout the major nations of the US bloc, reaching a rhythm unequalled since the great depression of the 1930s.

But bankruptcies are only an aspect of an equally significant phenomenon: the accelerating concentration of capital. In the capitalist jungle, where solvent markets are increasingly scarce, only the most modern companies, those able to produce at the lowest price, can survive. But in the present period the modernization of the productive apparatus demands ever more gigantic concentrations of capital. Against the American (and even the Jap anese) giants the Europeans - divided and unable to agree on anything other than how best to attack the proletariat - are less and less able to keep up in the technology race. It is easier and more profitable for a European company in diff iculty to make an alliance with US or Japanese capital than with other Europeans. And this is what happens in reality, despite the passionate declarations of the high priests of ‘United Europe’.

The EEC has been a unified market essentially for American and Japanese capital, which have the power or the material means to control a market of this size.

After years of effort, the EEC is only able to plan and organize the destruction and dismantling of the productive apparatus (the steel industry is only the most spectacular example).

From the standpoint of its objective conditions, Western Europe is turning into a social powder keg thanks to the acceleration of the economic crisis. But this is not the only reason. Two characteristics of capitalism in Western Europe make the class struggle particularly explosive and profound in this part of the world - the weight of the state in social life and the juxtaposition of a series of small nation-states.

The state’s weighting in social life makes the workers’ struggle more immediately political

The greater the state’s presence in economic life, the more each individual’s life depends directly on state ‘politics’. Social security, pensions, family allowances, unemployment benefit, state education, etc all make up a large part of the European workers’ wages. And this part is directly managed by the state. The greater the presence of the state’s institutions, the more the state is the boss of the whole working class. In these conditions, ‘austerity’, the attack on wages, takes on a directly political form and obliges the proletariat (in fighting back) to confront more directly the political heart of capital’s power.

With the development of the crisis, the class combat thus opens more immediately onto a political ground in Europe than in Japan or America. It is the governments, more than private companies that take the decisions that modify the workers’ conditions of existence. Austerity in Europe is the German government reducing scholarships and family allowances, the French government cutting unemployment benefit, the Spanish government proposing to lower the pension rate from 90% to 65%, the British government slashing the jobs of more than half a million state employees, the Italian government deciding to destroy the sliding wage-scale.

The weight of the state has grown regularly in all the Western bloc countries, including Japan and the USA. We can measure this weight in terms of the state administration’s total spending taken as a percentage of GDP. Between 1960 and 1981, this percentage grew from 18% to 34% in Japan and from 28% to 35% in the US. But at the same time, in 1981 it rose to:

47% in Britain

49% in Germany and France

51% in Italy

56% in Belgium

62% in Holland

65% in Sweden

This is one of the reasons that workers’ struggles in Western Europe tend, and will tend, to take on more immediately their political content.

The juxtaposition of several states makes the international nature of the proletarian struggle more obvious

Like wage-labor, the nation is a basic, characteristic institution of the capitalist mode of production. It constituted an important historical step forward, putting an end to the scattered isolation of feudal existence. But, like all capitalist social relations, it has now become a major barrier to any further development. One of the fundamental contradictions that historically condemns capitalism is the contradiction between the world scale on which production is carried out, and its national appropriation and orientation.

Nowhere in the world is this contradiction so striking as in old Western Europe. Nowhere does the identity of interests between proletarians of all countries, the possibility and necessity of the internationalization of the class struggle against the absurdity of the capitalist economic crisis, appear so immediately.

This generalization of the workers’ struggle across national frontiers will not happen overnight. It cannot be a mechanical response to objective conditions. A long period of simultaneous struggles throughout the small European countries will certainly be necessary for the working class to forge, from the boiling crucible of the prerevolutionary period, the consciousness of its international and revolutionary being, and the will to assume it. For this, the working class in Europe has the determining advantage of the greatest historical experience and revolutionary tradition. It is no accident if the proletariat’s main revolutionary political organizations are concentrated in Western Europe. Weak though they may still be today, these organizations have and will have a determining role to play in the revolutionary process.

The collapse of the capitalist economy is a planetary phenomenon affecting every country, creating the conditions for the world communist revolution. But it is Western Europe that, because of its place in the world productive process, its special position within the American military bloc, its political structure (importance of the state and multiplicity of nation-states), and the subjective conditions of proletarian existence, is necessarily at the epicenter of the world revolution.

RV

1 See ‘The Proletariat of Western Europe at the Heart of the Generalization of Class Struggle’ (IR 31, 4th quarter, 1982) and ‘Critique of the Weak Link Theory’ (IR 37, 2nd quarter, 1984)

2 Russia’s relative backwardness in relation to certain countries of its European slope, like the GDR, reflects the burden of its military costs. The only sectors where the USSR leads its bloc are the military ones.

3 The growing difficulties of American banks and the proliferation of bank failures are the first signs of the disaster that such a policy must lead to.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace