Submitted by ICConline on

After the replacement of President Sarkozy by Hollande in France, and the electoral slump of the parties of the outgoing Greek government, a commentator in the Guardian (8/5/12) was not alone in declaring that “Revolt against austerity is sweeping Europe.” Leftists saw “a growing backlash against austerity across Europe” (Socialist Worker 12/5/12), “deep popular opposition to austerity measures” (wsws.org 8/5/12) and even declared that “Europe turns left” (Workers Power May 2012).

In reality, whatever the level of dissatisfaction felt at election time, the ruling bourgeoisie will continue to impose and intensify its policies of austerity. Voting against governments can happen because of the depth of discontent, but it doesn’t change anything. For the working class it’s only through the mass organisation of its struggles that anything can be achieved. The election game is played entirely on the bourgeoisie’s terms, but workers still troop into the polling stations (if in decreasing numbers) because they still have widespread illusions in what could be achieved. There’s still a belief that elections can somehow be used as a means for social change, or that there are alternative economic policies that the capitalist state could follow. There has been no ‘revolt’ across Europe expressed in these elections, although there is definitely a lot of anger which has been impotently misdirected into the various democratic mechanisms. Having said that, if you actually examine what’s happened in recent elections they do reveal a lot about the capitalist class and the state of its political apparatus.

Not just the usual seesaw

Since the financial crisis of autumn 2008 a number of individual leaders and political parties have been replaced because of their identification with public spending cuts, job losses, wage and pension reductions, and all the other aspects of economic ‘rigour’ and austerity. There is no overall bourgeois strategy, just the removal of parties and individuals and their replacement by others, whether from the left or the right or by coalitions. The ruling class is just reacting to events without a clear idea of how it will arrange its political forces in the future. And it’s not taking long for the new leaders to begin to be discredited as they are exposed as being in continuity with their predecessors.

In November 2008 John McCain was defeated by Barack Obama in the US Presidential election partly because of his connection with the policies of George Bush and the fact that the US economy had been in recession since late 2007 in a crisis deeper than anything since the 1930s.

In the UK, following the general election of May 2010, the Labour Party was replaced by a Conservative and Liberal Democrat government, the first coalition since the Second World War. The British bourgeoisie, usually so assured in its political manoeuvres, was not able to accomplish its usual Labour/Tory swap. Since the election it has also had difficulties in presenting Labour as a viable ‘alternative’.

In Belgium it took 18 months from the election of June 2010 before a government was finally formed.

In the general election in Ireland in February 2011, Fianna Fail, the party that had been the largest since the 1920s, saw its proportion of the vote go from 42% to 17%. The Irish government is now a Right/Left coalition of Fine Gael and Labour. Ireland was in recession in 2008 and 2009. It returned to recession in the third quarter of 2011. The new government has predictably shown itself no different from the previous FF/Green coalition. The myth of the ‘Celtic Tiger’ faded out a long time ago.

In the Portuguese legislative elections of June 2011 the governing Socialist Party saw its support go from 37% to 28%. Electoral turnout declined to a historically low level of 58%. Unemployment continues to rise, up to more than 13%, having been less than 6% in 2002. Portugal is in its worst recession since the 1970s. The conditions for its 2011 bailout from the EU and IMF have meant a vicious series of government spending cuts.

In the Spanish general election of November 2011 the votes for the ruling Socialist Party went from 44% to 29%, and there was growing support for minor parties. Under the conservative People’s Party Spain has fallen back into recession. Unemployment, which has been growing throughout the last five years, has reached record levels with a 24.4% jobless rate (over 50% of under 25s), the highest figures in the EU.

In Italy in November 2011 Silvio Berlusconi was replaced by a government led by economist Mario Monti. His cabinet was constituted of unelected ‘technocrats’. He has introduced a range of austerity measures – with the support of most of both Italian houses of parliament.

In Slovenia in December 2011 there was a parliamentary election in which a new party, Positive Slovenia, that had only been founded in late October, got the highest proportion of the vote. After a period of manoeuvres and negotiations the outgoing 4-party coalition was replaced by a 5-party coalition which only had a Pensioners’ Party in common, but not Positive Slovenia. With the Slovenian economy is in recession, a new programme of austerity measures was adopted by the Slovenian Parliament on 11 May. Major unions which had staged demonstrations against the programme have said they would not oppose it with a referendum. Last year four pieces of legislation were rejected by referendum.

In presidential elections held in Finland in January and February this year the long period of the decline of the Social Democratic Party reached a new low point. The new president is the first in 30 years not to be a Social Democrat. Voter turnout was the lowest since 1950.

In the Netherlands in April this year the coalition government resigned after only 558 days in power. The parties have been in dispute over budget cuts.

In the recent French Presidential election Hollande’s victory was in many ways due to his not being Sarkozy. Despite his claims to have a different approach on questions such as investment he will have no choice but to continue the attack on living and working conditions. Hollande said before his first visit to Angela Merkel that he would bring "The gift of growth, jobs, and economic activity." Although this is the usual politician’s hot air, corresponding to no material reality, at least the situation in France is by no means as desperate as that in Greece.

Greek politics in a mess

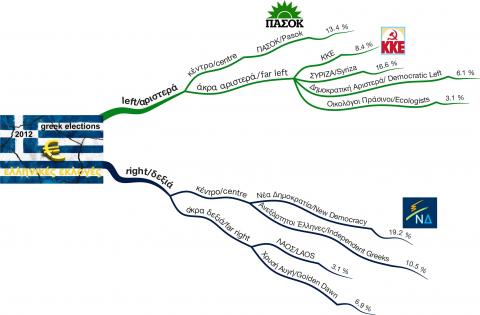

Following the latest elections in Greece it was clear the parties of the PASOK/New Democracy/LAOS coalition had lost the most support. It should be recalled that the coalition had only been installed last November, to replace George Papendreou’s government and implement the measures required by the IMF/EU/ECB. In the elections, despite there being a choice of 32 parties, there was a significant reduction in the number of people voting to a lowest ever figure of 65%. This contrasts with the previous low figure of 71% in 2009 and previous figures in the high 70s or even more than 80% that Greece was used to. If the French election result mainly expressed opposition to Sarkozy, the Greek result showed mainly opposition to the government coalition and the measures it had undertaken. The fact that the Greek parliament now has four parties of the Left and three of the Right where once it was dominated by PASOK/New Democracy shows the degree to which the bourgeoisie’s political forces have splintered. The prospects of a new coalition without a new election seem limited.

There has been a lot of attention in the media on the role of the leftwing coalition Syriza, portrayed as a new force without whose co-operation or tolerance no government could function. Because they claim to be against austerity they will, for the moment, quite possibly continue to increase their support. However, whether they operate as a buffer between government and striking workers, or actually join a government coalition, they do not represent anything new. Along with its anti-austerity phrases Syriza has clearly stated that Greece should remain in the EU and the euro, debts can not just be written off, but it would prefer some more benign conditions for receiving the latest bailout.

Where the emergence of Syriza is a sign of some residual flexibility from the bourgeoisie, the sharpest evidence of the decomposition of Greek capitalism’s political apparatus is seen in the gains made by Chrysi Avgi (Golden Dawn) at the expense of LAOS. Greece has had right wing parties before (LAOS is the most recent example), and in Metaxas they had a real dictator in the late 1930s, the contemporary of Hitler, Mussolini, Franco and Salazar. However, Chrysi Avgi isn’t just another racist, right-wing party demonised by the Left. It’s anti-immigrant policies are backed up by physical attacks on foreigners. It has also mounted attacks on its political opponents, tried to intimidate journalists and has links with Nazi groups.

Chrysi Avgi campaigned on the slogan “So we can rid the land of filth” with candidates claiming to be more soldiers than politicians. They claim to be ‘Greek nationalists’ in the mould of Metaxas, rather than being neo-Nazis. You could be forgiven for being confused on this when you see the black symbol on the red background of their party flag. It looks very similar to a swastika, although it is in fact a ‘meander’ or ‘Greek fret.’ Whatever label you want to pin on them, Chrysi Avgi are clear evidence of the further decay of bourgeois politics. Parties in Greece that support the return of the monarchy are barred from standing at elections, but Chrysi Avgi has 21 members in the new parliament.

The Greek elections are the most obvious example of how the bourgeoisie across Europe is coping politically with the economic crisis. It can’t offer any genuine economic alternatives to austerity, but it is also using up its political alternatives as parties take their turns to impose programmes that will not challenge the impact of the economic crisis. There is no particular political strategy, just a day-to-day reaction to events. Bourgeois democracy continues to function, but the ruling class has a decreasing variety of ways to deploy its political apparatus. The number of people who are voting is in decline; new parties and coalitions are emerging to cope with changed situations. But, for the working class there is nothing to be gained by the replacement of one government by another, or in any participation in the democratic game.

All the political parties are factions of one state capitalist class. This is one of the reasons that democracy is so important for the bourgeoisie, because it gives the illusion of offering a number of different choices. For the working class only struggle on its own terms can set in motion a force that can break the social stalemate between the classes. The bourgeoisie has nothing to offer, not in its economy, and not in its elections. The working class can only rely on its self-organisation, on a growing consciousness of what’s at stake in its struggles.

Car 14/5/12

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace