Submitted by ICConline on

Below is the translation of an article written by our comrades in Mexico and published in Spanish in number 133 of Revolución Mundial (March-April 2013).

The terror and the degeneration of the Russian Revolution are often explained solely through the personality of Stalin, an uncouth individual, a careerist and an adventurer. It is certain that his character was an important factor in the historical role played by Stalin, but not the only one.

60 years ago, on 6 March 1953, the world press announced the death of Stalin. “The mad dog is dead, the madness is over”, was the popular adage employed in Spanish-speaking countries. But in the case of Stalin, such a statement was unjustified. If Stalin was at the helm of the physical and moral destruction of a whole generation of revolutionaries, if he openly contradicted all the internationalist principles of marxism and if he has been the leader of one of the major imperialist powers that presided over the division of world, his death in no way eliminated or halted the counter-revolutionary dynamic that he largely contributed to in his lifetime. This confirms that his role as a major player in the counter-revolution was made possible by the failure of the world revolution to extend. It was the isolation of the revolution that directly produced the degeneration of the Bolshevik Party and its transformation into a state party putting national interests above those of the world revolution.

The grim legacy of Stalin has served and continues to serve the interests of the ruling class. Winston Churchill, a well known figure of the exploiting class and bitter enemy of the proletariat, paid tribute to the services rendered by Stalin to the bourgeoisie, saying he “will be one of the great men in Russian history”.

Stalinism, the incarnation of the bourgeois counter-revolution

In the revolutionary wave that emerged during and after the First World War, it was the Russian proletariat at the head of the revolution of 1917 that produced the most powerful dynamic of the international wave. The process continued in 1918 when the battalions of the German working class rose up, seeking to spread the revolution, but they were ruthlessly crushed by the German bourgeois state led by Social Democracy with the broad collaboration of the democratic states. Attempts to spread the proletarian revolution were thus stifled and the triumphant Russian revolution became isolated. The bourgeoisie of the whole world then erected a cordon sanitaire around the proletariat in Russia, making it impossible to hold on to the power it had seized in 1917 It was under these conditions that the counter-revolution arose from within: the Bolshevik party lost all its working class vitality, fostering the emergence and dominance of a bourgeois faction that was lead by Stalin.

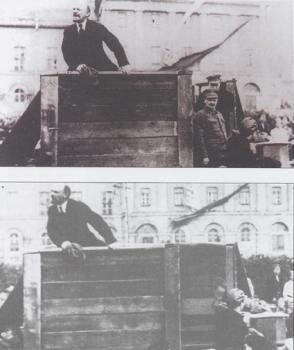

Therefore, Stalinism is not the product of the communist revolution but rather the product of its defeat. Following to the letter the advice provided by Machiavelli, Stalin had no hesitation in resorting to intrigue, lies, manipulation and terror to install himself at the head of the state and to consolidate his power, strengthening the work of the counter- revolution by resorting to acts as ridiculous as rewriting history, doctoring photos by eliminating from them certain personalities he regarded as ‘heretics’ because of their oppositional stand. At the same time he promoted the cult of his personality and distorted the truth about the scale of repression and making this the core of his policy. This is why Stalinism is in no way a proletarian current; it is quite obvious that the means used and objectives pursued by Stalin and the group of careerists he surrounded himself with were overtly bourgeois.

With the ebbing of the revolutionary wave of 1917-23, the counter-revolution opened the door to the actions of Stalin. Thus, persecution, harassment and the physical elimination of combative proletarians were the first services he rendered to the ruling class. The world bourgeoisie applauded his methods, not only because an important generation of revolutionaries was wiped out but also because it was done in the name of communism, tainting its image and throwing the whole working class into total confusion.

The charges trumped up by the political police, the use of concentration camps and other atrocities, were supported by all the democratic states. For example, even before the trial of Zinoviev and Kamenev (in 1936) in which threats against their families and physical torture were used, the democratic states applauded the services that Stalin rendered to their system: through the medium of their ‘worthy’ representatives assembled at the League of Human Rights (headquarters in France), the bourgeoisie approved the perfect ‘legality’ of the purges and the trials. The declaration of the novelist Romain Rolland, Nobel Prize for Literature winner in 1915 and distinguished member of this organisation, is indicative of the attitude of the ruling class: ‘“there is no reason to doubt the accusations against Zinoviev and Kamenev, individuals discredited for quite some time, who have twice been turncoats and gone back on their word. I do not know how I could dismiss as inventions or extracted confessions the public statements of the defendants themselves.”

Similarly, before the forced exile of Trotsky and his subsequent hounding across the world, the Social Democratic government of Norway and the French government, in total complicity with Stalinism, did not hesitate to harass and ultimately expel the old Bolshevik.

‘Socialism in one country’ - the negation of marxism

The full extent of the decline of the Bolshevik Party was revealed in when Stalin introduced the doctrine of the possibility of building socialism in one country.

Immediately after Lenin’s death in January 1924, Stalin hastened to place his pawns into key positions in the party and to focus his attacks on Trotsky, who was, after Lenin, the most respected revolutionary, and in the front line of the organised mass mobilisation of October 1917.

One proof of the departure of Stalin from the proletarian terrain is in formulating, along with Bukharin, the thesis of ‘socialism in one country’. (Let’s not forget that, some years later, Stalin would have Bukharin executed!). As the self-proclaimed ‘supreme leader of the world proletariat’ and the official voice of marxism, the best service that Stalin provided to the bourgeoisie was precisely this ‘doctrine’ that distorted and perverted proletarian internationalism, that had always been defended by the workers’ movement. This policy discredited marxist theory, spreading and sowing confusion not only among the generation of proletarians of that period but also today amongst the current generation. For example, we are cynically presented with facts like the invasion of Czechoslovakia (1968), the crushing of the Hungarian uprising (1956), or the invasion of Afghanistan in the 1980s, as expressions of ‘proletarian internationalism’. A character like Che Guevara claimed that the shipment of arms to countries like Angola was a demonstration of proletarian internationalism. This is not at all a confusion but is a deliberate policy aimed at demolishing this central pillar of marxism.

In the Principles of Communism (1847), Engels clearly defended the internationalist argument attacked by Stalin : “Will it be possible for this revolution to take place in one country alone? No. By creating the world market, big industry has already brought all the peoples of the Earth, and especially the civilised peoples, into such close relation with one another that none is independent of what happens to the others.

Further, it has co-ordinated the social development of the civilised countries to such an extent that, in all of them, bourgeoisie and proletariat have become the decisive classes, and the struggle between them the great struggle of the day. It follows that the communist revolution will not merely be a national phenomenon but must take place simultaneously in all civilised countries (…) It is a universal revolution and will, accordingly, have a universal range”.

The Bolsheviks, with Lenin at the helm, conceived the revolution in Russia as a first battle in the world revolution. That is why Stalin was lying when, to validate his thesis, he said it was a continuation of the teachings of Lenin. The bourgeois nature of this ‘theory’ dug the grave of the Bolshevik party and also that of the Communist International by subjecting these bodies to the defence of the interests of the Russian state.

Stalinism, an important pillar in the reconstruction of the bourgeoisie in the USSR

The growth of terror through the concentration camps and the surveillance, control and repression organised through the NKVD (the secret police), etc., symbolise the counter-revolutionary juggernaut oiled by Stalin. But this is only the backdrop to the profound role it would fulfil: permitting the reconstitution of the bourgeoisie in the USSR.

The defeat of the world proletarian revolution and the disappearance of all the proletarian life from the Soviets provided the conditions for the establishment of a new bourgeoisie. It is true that the bourgeoisie was defeated by the proletarian revolution of 1917, but the subsequent ruin of the working class allowed Stalinism to rebuild the ruling class. The bourgeoisie’s reappearance on the social scene did not come from the resurrection of the remnants of the old class (except in a few individual cases), or from the individual ownership of the means of production, but in the development of a capital that would appear depersonalised, with no individual faces, only in the incarnation of the party bureaucracy merged with the state, that is to say, under the form of state ownership of the means of production.

For this reason, assuming that the nationalisation of the means of production is the expression of a society different to capitalism or that it represented (or represents) a ‘progressive step’ is a mistake. Thus when Trotsky in The Revolution Betrayed explained that “state ownership of the means of production does not change cow dung into gold and does not confer an aura of holiness on the system of exploitation”, he went on to insist on the fact that the USSR was a ‘degenerated workers’ state’, which was an implied appeal for its defence. This was from the outset a profoundly confused conception. Trotskyism, above all after Trotsky’s death, pushed this logic to its extreme by dragooning the working class behind the defence of one imperialist camp, that of the USSR, during the Second World War, which demonstrated the Trotskyist current’s abandonment of the proletarian terrain.

In fact, the behaviour of Stalinism during the Second World War openly demonstrated its bourgeois nature: in 1944 ‘the Red Army’ cynically stood by while the Nazis crushed the Warsaw Uprising and, together with the Allies, participated in the re-division of imperialist spoils at the end of the war.

The bourgeoisie pays tribute to the butchers of the imperialist war

As we said above, the world bourgeoisie has received and still benefits from the great service provided by Stalinism, even if hypocritically, it distanced itself from Stalin, calling his government evil, while not hesitating to use it to fuel patriotism and to justify the imperialist war of 1939-45. This policy has by no means exhausted itself.

The year 2012 was marked by an acceleration of the struggle in Georgia (formerly part of the USSR) between bourgeois factions. As part of this bourgeois quarrel, there was a return to invoking Stalin to feed a nationalist campaign .

At the end of 2012 and the first months of this year, the Georgian bourgeoisie, under the pretext of recovering its historical legacy, restored statues of Stalin to several cities. The Georgian bourgeoisie (mainly the ultra-nationalist party Georgian Dream) revived his memory for the sole reason that he was born in this region, but more particularly to spread numbing propaganda among the exploited and chain them to the defence of the local bourgeoisie.

Similarly, changing the name of the city of Volgograd to Stalingrad for six days during the festive commemoration of ‘the defense of Stalingrad’, more than just a provincial act, must be understood as a justification by the bourgeoisie of the imperialist war which ennobles the role played by butchers like Stalin.

But if the bourgeoisie pays tribute to the memory of its bloody guard dogs, the working class needs a better understanding of the world and how to change it. It needs to reclaim its own history and learn from its own experiences and to better recognise the anti-proletarian profile of Stalin and Stalinism; it has, above all, to discover the internationalist principles of marxism that the bourgeoisie has persistently distorted and attacked, because they are the key to real class action.

Tatlin, February 2013

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace