Submitted by ICConline on

The following article is one of several through which we plan to deal with the rise of China and its consequences for imperialist relations worldwide. For reasons of space we will focus in this article on the New Silk Road. In future we look in more detail at Chinese ambitions in Africa and Latin America and examine its overall rivalry with the US.

“For now however, China is not looking for direct confrontation with the US; on the contrary, it plans to become the most powerful economy in the world by 2050 and aims at developing its links with the rest of the world while trying to avoid direct clashes. China’s policy is a long-term one, contrary to the short-term deals favoured by Trump. It seeks to expand its industrial, technological and, above all, military expertise and power. On this last level, the US still has a considerable lead over China”. ICC Report on Imperialist Tensions, June 2018

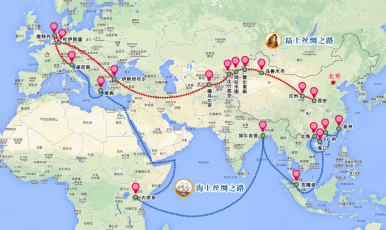

In May 2017 with the presence of 27 heads of states or governments the Chinese President Xi Jinping announced the “One Belt One Road” (OBOR) project also called the “New Silk Road”. This project is composed of two elements: the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB), and Maritime Silk Road (MSR). This project involves around 65 countries, making up for 60% of the population of the planet and around 1/3 of the GNP of the world. The Chinese president announced investments over a period of the next 30 years (2050!) up to 1.2 trillion dollars. This is not only the biggest economic project of this century, but it is also the outline of the most ambitious imperialist projects that China has made public. Behind this Xi Jinping declares the goal of overtaking the US and becoming world power number one by 2050.

This project corresponds to the ambitions of China to reconquer its old leading position in the world – which it occupied until the penetration of the capitalist powers into China in the early 18th century.[1] With this proclaimed goal China aims at the biggest shift in the imperialist power constellation for more than a century. The Silk Road project is only one, albeit essential, move in China’s ambitions. After having expanded massively on an economic level, China also began laying a “String of Pearls” in the Indian Ocean, allowing China to encircle India via Burma, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Pakistan and the Maldives. After this maritime expansion, the Silk Road project aims at a new overland expansion on the Asian Continent.

China has become the most populous country on the planet: almost 1.4 billion people live there (India ranks second with 1.32 billion). It is the second economic power in the world and in many branches it has already become number one; and it has the third largest land mass. After more than three decades of capitalist modernisation and opening-up, China has become the world's largest trading country, e-commerce country, and consumer market. Between 1979 and 2009, in thirty years, Chinese GDP in constant 2005 dollars has grown from about 201 billion to about 3.5 trillion; Chinese exports have grown from almost 5% of their share in GDP to about 29%; imports from about 4% to 24%. Trade surpluses have led to a large growth in China’s reserves, which has allowed Chinese capital to move out for investments, mergers and acquisitions and to become an important FDI[2] source on the world’s financial stage. It is expected that by 2030 China will account for one fifth of the global economic output of the world. The country has been investing massively in the most modern industrial techniques such as quantum technology and Artificial Intelligence (AI). As for its military expenses they amount to the total of all European countries put together. No other country could entertain such ambitions, and no other country could develop such a vision, stretching out its tentacles across the Asian continent. For the moment not through direct military occupation (except for the coral reefs in the South China Sea) but through building an economic network with a whole geo-strategic policy behind it: developing new infrastructure, implanting outposts, forging privileged links. Chinese ambitions are shaking the entire imperialist constellation and not only in the surrounding Asian area: it has an impact on the Pacific countries, on the Indian Ocean, on Africa, on South America, on Europe and of course on its relationship with the US. In short, it has the most far-reaching international and long-term repercussions. At the same time, its ambitions will bring it into conflict not only with the US, but also with other countries. Already resistance has been gathering from some of its closest neighbours (Vietnam, India, Japan), and China’s plans will also pose a new challenge for Russia. This project also aims at thwarting any possibility of strangling China by blocking maritime transport in the strait of Malacca or the South China Sea. By establishing railway connections to Iran, Pakistan, Burma and Thailand China hopes to circumvent possible means of strangulation or to alleviate some of the worst effects.[3]

The New Silk Road project will be linking China via Central Asia and Russia with Europe, and the maritime connection will allow it to establish new links with Africa and Europe through the China Sea and the Indian Ocean. Six corridors between China and Europe are to be established.

The first major corridor: railway connection and pipelines connecting China and Europe via Mongolia, Russia and Kazakhstan.[4]

The other two major corridors: Western China – via Central Asia – and the Middle East towards Turkey via Iran; and the China-Pakistan corridor linking it to the Indian Ocean.[5] Three of the six corridors pass through the Central Asian part of Xinjiang.

In addition three “secondary” corridors will be connecting a) China-Mongolia-Russia, b) Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar (BCIM), c) China-Indochina – (through northern Laos – stretching into Thailand, Vietnam and Malaysia-Singapore -i.e. to South East Asian waters). In Asia a railway line of 873 km is to establish a link between China and the Thai coast.

In Africa China has financed and constructed a railway line between Djibouti and Addis Ababa (Djibouti Silk Road Station); it will be financing a railway line of 471 km in Kenya between the capital Nairobi and the port of Mombasa on the Indian Ocean. The long-term goal is to establish a network of railway connections between the new port of Lamu (Kenya), South Sudan, and Ethiopia (LAPSSET). Following Kenya, Ethiopia, Egypt and Djibouti, Morocco has also started cooperating in the New Silk Road project.[6]

A whole chain of ports and big investment projects is to offer the logistical basis for further investments in the area.

In addition to the overland railway connections, and building on the “String of Pearls”, the Maritime Silk Road is the second plank of the mega-project, which requires the expansion and construction of ports along the main sea routes connecting China via the South China Sea, the Malacca Strait, the Indian Ocean to the coasts of Africa. Plans in the Arctic of an “Ice Silk road” to establish a short cut between the Pacific Ocean and the Atlantic along the Northern Siberian route, as well as plans to build a second canal in Central America through Nicaragua, are part of the global Chinese strategy.

Furthermore, China also plans to build fibre optic cables, international trunk passageways, mobile structures and e-commerce links along its Silk Road corridors. While this will certainly boost connectivity and information exchange, it can easily enable China to carry out electronic surveillance and increase its cyberspace presence, raising its espionage capabilities…

An enormous gamble

Of course this “master plan” will need a long time to implement and it faces a number of obstacles. The capacities of resistance by other powers are impossible to assess realistically at the moment. However, the Chinese State seems to be ready to throw maximum resources at it:

- China’s state-owned commercial banks are being pushed to supply money for the government plans;

- the State controlled China Development Bank (CDB) and Export-Import Bank of China (EXIM) have already provided $200 billion in loans to several of the countries participating in the project;

- CDB and EXIM have imposed debt ceilings for each country and set limits on borrowers’ credit lines;

- most infrastructure loans were negotiated primarily between governments with interest rates below the commercial ones. For example CDB offered Indonesia a 40-year concessionary loan, without insisting on Indonesian government debt guarantees to finance 75% of the $ 5 million Jakarta-Bandung railway;

- China has facilitated loans to countries that would have difficulty getting loans from Western commercial banks;

- 47 of China’s 102 government-owned conglomerates participated in more than 1600 Belt and Road projects;

- the China Communications Construction Group snatched $40 billion of contracts.

And so forth … So while this may be seen as a huge economic and financial gamble, it certainly reflects the determination of the Chinese state to fortify its position at all costs. At the same time, the project, whose implementation is planned over a period of 30 years, will have to face the storms of world-wide escalations of the economic crisis, trade wars, political turbulences and the growing resistance by China’s rivals – from the US to a number of other countries.

In short, all the mounting contradictions of the capitalist crisis and the sharpening antagonisms between the US and China make it impossible to answer the question whether the project will ever be completed. Not to mention the unpredictable development of the Chinese economy and its financial resources in the long-term.

In addition, the speed with which China built its railway lines within China during the past years – with the State mobilising all sorts of resources and brushing aside any ecological doubts or resistance from the local population – will not be easily duplicated on an international level. Several of the projects pass through areas under attack by jihadists. And a number of countries participating in the project will be piling up so many debts implying that any future financial storms may mean the end of their solvency. For example, building the Kunming-Singapore Railway through Laos will cost the country $6 billion, nearly 40% of GDP of Laos in 2016. Pakistan’s external debt has risen by 50% over the past three years, reaching nearly $100 billion, and around 30% of that is owed to China. Turkmenistan is facing a liquidity crunch due to debt payments to China. Tajikistan has sold the right to develop a gold mine to a Chinese company in lieu of repaying loans. And many of the participating countries have been marked and will be marked by political instability, civil unrest and armed conflict.

However, while the question marks hanging over the project are almost endless, these high risks have not prevented the Chinese government from drafting this plan.

China’s re-emergence in the context of decomposition

The fact that China is now openly putting forward such ambitions is based on the new position which China occupies in the world economy and in the imperialist pecking order. As we have developed in previous articles[7] China had been a world leading power until the turn of the 18th century, when it was dismembered mainly by the European colonial powers Britain and France, and when it was partly occupied by Japan until 1945. When Mao Zedong took power in 1949, the Chinese state did not have the means to revive the old Chinese ambitions. In the context of a long period of dependence on Russia, the Peoples’ Republic of China desperately tried to overcome its backwardness. Already in the early 1950s in the Korean war it showed its desire to break US domination in the region, and later, in the 1960s, China began to clash with India, and above all with Russia. In relation to Russia and the US China was the underdog for decades. Neither the “Great Leap Forward”, nor its decade-long autarky, nor the Cultural Revolution in the mid-1960s enabled it to develop the power to compete with its bigger rivals. And the division of China into Taiwan and mainland China, the permanent stand-off with the US over Korea, in Vietnam and the Pacific (Taiwan, Japan), the year-long conflict with Russia along the Ussuri River, left China surrounded and dead-locked on the geo-strategic and military level.

However, having suffered a military humiliation at the hands of the much smaller Vietnam in the 1979 conflict, the Chinese army was determined to modernise its forces. And in the context of a collapsing Stalinist regime in Russia and Eastern Europe, the Chinese Communist Party resolved to adapt the country to the new conditions which have existed since 1989. Its spectacular economic growth and its determination to reconquer its position in a world where the US has been on the decline for decades, meant that China would have to throw in its economic weight to translate this into geo-strategic, imperialist triumphs.[8]

Its prodigious economic development of the last few decades unleashed a strong push for putting forward its interest on the imperialist chessboard, which since the late 1980s has been marked by: a) the fact that the former Soviet bloc began to fall apart and imploded in 1991 and b) the US - as the only remaining super-power – has and is being undermined and challenged in many areas; by India, Iran, Turkey and many other countries advancing their own imperialist ambitions. In other words, a world where there has been a “free-for-all” of imperialist tensions. The confrontation between the US and China in the region is but one polarisation (even though the most dangerous in the long-term) in the midst of an increasingly complex minefield of imperialist tensions.

The New Silk-Road – only an economic project?

For two decades the Chinese economy recorded very high growth figures, in some years even double-digit growth rates. These have now slowed down (in 2017 to 6.5%) and it is undeniable that the New Silk Road project is also a response to these difficulties. Chinese national capital must find more outlets for its gigantic overproduction. In particular in the branches developing infrastructure, or the sectors of iron and steel, cement, and aluminium, overproduction is at its highest. Between 2011 and 2013 China produced more cement than the US during the entire 20th century. With insufficient demand on the Chinese market Chinese companies must at all cost find outlets abroad.

Infrastructural projects offer not only the necessary logistics for conquering new markets and installing new corridors for the transport of troops; they also require massive investments themselves. Of the 800 million tons of steel produced in 2015 by Chinese state-run companies, 112 million tons were exported at giveaway prices, because sales possibilities have shrunk on the internal market. Thus with the new Silk Road project the Chinese state is launching one of the biggest ever state capitalist interventions to boost the ailing economy. And the Chinese state has planned to invest the most massive financial resources to achieve this. China is said to have already released $1000-$1400 billion for the first financing of the Silk Road projects, but the total cost is expected to amount by 2049 (the year of 100 years of existence of the Peoples’ Republic of China) to twice the size of the present GNP of China If we compare the amount of funds already available, proportionately they supersede by far the USA’s Marshall Plan funds of 1948, through which the US granted $5 billion in aid to 16 European nations[9].

Unlike Russia and the US, China can still mobilise such enormous amounts. Russia never disposed of such funds, largely because of the weight of the war economy at the time of the Cold War and its traditional “backwardness” linked to the mechanisms of Stalinist rule.

Russian capitalism under Putin has not become more competitive on the world market. The strong dependence on the income it generates through energy resources and the weight of its war economy mean that it simply does not have the funds to develop projects comparable to the New Silk Road. And the US, also, among other reasons, as a result of its gigantic military expenses, can no longer play its “financial joker” as it could in the past. In many sectors US industry is lagging behind and in many areas parts of its infrastructure are derelict. Thus China is presently the only country able to make such colossal amounts available, even if much of this is financed with state seconded credits. But while the past two decades allowed for China’s dizzying ascent, future conditions of the development of world capitalism are unlikely to offer the same advantageous framework for China.

Can we compare the construction of such a new gigantic railway network across Asia and in other continents to the role which the construction of the railways played in the expanding phase of capitalism in the US in the 19th century?

As Rosa Luxemburg developed in her writings (The Accumulation of Capital and An Introduction to Political Economy) the construction of the railways in the US and their advance to the Far West was accompanied by the conquest of land from the native population through a combination of force and the penetration of commodity relations. The railways pushed into a zone dominated by pre-capitalist production. The combined efforts of the railway companies, the state with its judicial apparatus and its armed forces, began to eliminate any local resistance and paved the way for the integration of the area into the capitalist system. With the construction of the Silk Road railways across Central Asia and elsewhere, it is true that some areas which have hitherto been in the periphery, or even existing outside of the capitalist market, will be faced even more with a flood of Chinese products. And since Chinese workers have been often been engaged in the construction of infrastructure or other major projects, probably only a small portion of the local population will find (temporary or permanent) jobs thanks to these new transport corridors. On the whole this construction is unlikely to have an economic spin-off similar to the extension of the US railways had in the 19th century. The most likely scenario is that of a widespread ruin of local producers and shop owners crushed by more competitive Chinese products...

Competition between China and Russia

China’s economy is about eight times larger than Russia’s (and its population is 10 times larger), but China is extremely dependent on energy supply from abroad, and Central Asia plays a particularly vital role for China’s energy supply.

The Chinese state is trying to reduce its dependence on energy delivered by Russia (it receives 10% of its oil and 3% of its gas from Russia). And China is now aiming to secure new energy supply routes to its west, by-passing the dangers hanging over the Middle East and the transport routes from there to China. 43% of Chinese oil and 38% of gas consumption come from Saudi Arabia. The maritime transport passes along the coasts of Hormuz, Aden and the straits of Malacca, all within the reach of the US 5th and 7th fleets, stationed in the Indian and Pacific Ocean. In other words, China is attempting to make the energy resources of Central Asia more accessible to its needs.

However any Chinese plans to establish closer links with Central Asia and beyond will profoundly alter its relationship with Russia. This comes after a period when, during the past 20 years, China has already been expanding its influence into Siberian territory to its north.

Since 1991 the Russian Far East (RFE) has lost about a quarter of its population. The number of Chinese immigrant workers in the RFE has gone by up 400,000 since January 2017, while Russia’s Far Eastern Federal District has lost two million people since 1991 (about a quarter of its population) as a result of higher death rates and emigration. Russia has been leasing land – hundreds of thousands of hectares – to Chinese companies and allowing cheap timber extraction. There is the possibility that the Chinese population will at some stage outnumber the Russian population and that Chinese commercial influence will become dominant. For Russian nationalists this means the goal of the Russian Czar when constructing the Siberian Railway - to keep control over Siberia and to be able to play a crucial role in Far East - is being threatened.[10] And after its expansion into the Russian Far East, with the new Silk Road project China is now launching another offensive to its west.

Up till recently, Russia could consider Central Asia as its “backyard” but now Russian trade with Central Asia has been falling continuously. In 2000 the Chinese share in trade with Central Asia was only 3%, whereas in 2012 it had risen to 25% - mostly at the expense of Russia.[11] Moscow’s means of avoiding further damage resulting from Chinese expansion are limited. Even before the project was announced officially by the Chinese president Xi Jinping, Russia had tried to stabilise its position in Central Asia by setting up, in 2014, the EEU (Eurasian Economic Union) which excluded China.[12]

But for the Central Asian countries the Silk Road project seems to be more attractive, because of the promise of Chinese investments in the region and more free trade. The Russian-dominated EEU only offers a tariff union, while Russia itself is short of funds. This sheds light on the chronic lagging behind of Russian capital. Russia has been trying to compensate for its economic inferiority through the increasing role of its military. But China is also acting as a growing rival to Russia on the military level in Central Asia. For example China has begun delivering military equipment to Central Asian countries. Common manoeuvres have begun between Chinese and Central Asian troops. Even though Russia still dominates the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO)[13] (Armenia, Belarus, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Russia belong to it), China has been declaring its intention of safeguarding security in the region, counting on its own forces. Negotiations have begun with Turkmenistan to open a military base in the country (the second after Djibouti). And China also engaged in a security alliance with Afghanistan, Pakistan and Tajikistan to fight terrorism. Military cooperation between Central Asian countries and China mark a turning point, because previously China had abstained from establishing a military presence and won sympathy among many regimes because of its “non-interference in the affairs of other countries”. Its policy of either keeping a low profile or acting more aggressively, as in the South China Sea, correspond to the “push” and “pull” tactics.

More globally the development of Russian-Chinese relations show the contradictory nature of their relationship, where one country has either been heavily dependent on the other (as China was on Stalin’s Russia in the early days of Mao,) or where they have been developing their rivalry and even directly threatening each other with mutual destruction (as in the 1960s). Each time both countries had major antagonisms with the US (even though temporarily, in the early 1980s, China supported the US in Afghanistan against Russia). Since 1989 China has aimed at a closer cooperation with Russia in order to counter the US wherever possible, and in an initial period China also received most of its weapons and military technology from Russia. This is changing.

China has also always used Russia as a source of energy. After the Russian occupation of Crimea and Russia’s hidden presence in Eastern Ukraine, China benefited from the Western sanctions against Russia. Looking for a counter-weight to the sanctions, Russia had to find markets in China, but China could put pressure on Russia and lower both Russian prices of energy products and receive concessions for investing in Russia. Thus while Russia scored points by occupying Crimea and being present in Eastern Ukraine, it paid a heavy price by getting somewhat blackmailed into bargain deals for China. This shows that the Russian war economy comes at a high price. At the same time, Russia, which feels threatened by the Chinese “invasion through the backdoor” in East Asia and its Silk Road ambitions westwards, is aware of the asymmetric nature of the relationship between the two rivals. The more China develops its own armaments industry and technology the less dependent it will be on Russian arms exports and arms technology transfers. China could not openly welcome the Russian occupation of Crimea, because it would have discredited China’s intransigence on territorial integrity – indispensable with regard to Uighur independence aspirations in Xinjiang. Russia is also in a dilemma vis-a-vis China’s expansion in the South China Sea (SCS), especially after China has more or less occupied a number of coral reefs in the South China Sea, transforming them into military bases. Military ties between Russia and Vietnam could also create tensions between China and Russia.[14]

However, as we have shown elsewhere,[15] Russia and China work together as much as possible against the US. The two countries have held common military manoeuvres in the Far East, in the Mediterranean and in the Baltic Sea. But the Silk Road project is certainly one of the Chinese schemes which will force Russia to react. At the same time it will push other countries to try and deepen any antagonistic interests between China and Russia.

With the Chinese advance in Central Asia, China has managed to benefit from the weakening of both the US and Russia in the region. Shortly after the collapse of the Soviet empire the US managed to develop privileged links and even to open some military bases in Central Asia. However, in the context of US decline worldwide, the US has also been losing ground in Central Asia – with China being the main beneficiary.[16]

But the Central Asian countries fear both Russian military hegemony and Chinese expansion and may try to gain as much as possible for themselves by taking advantage of divergent interests between Russia and China.

China’s push towards Europe is also driving a wedge between Europe and Russia

Since Europe presently absorbs 18% of Chinese exports, any improvement of trade connections would strengthen the Chinese position in Europe itself.[17] It is therefore particularly keen on speeding up freight traffic from the recently acquired port of Piraeus near Athens to Central Europe. The project of building a high speed train between Athens and Belgrade and further on to Budapest reflects China’s attempts to achieve a growing influence in Central Europe. China will use the Silk Road as a way of “sidelining” Russia (or if necessary enter into an alliance with it), in order to expand its position in Europe. This would at the same time threaten in particular the interests of European rivals in Central Europe itself, where Germany above all has achieved a dominant position. Reactions by German capital have already signalled that – in addition to the efforts to fend off Chinese attempts to get a stronger foothold in hi-tech sectors - German capital will counter-act the Silk Road project on different fronts. This may even mean that this will compel German capital or other national capitals to make tactical alliances against rising Chinese influence in the region. This brings in another unpredictable element - possible common steps by European countries together with Russia against China.

Turkey has also been a major target of Chinese investments. Chinese companies are involved in several of the megalomaniac projects of President Erdogan. Over the next three years the number of Chinese companies active in Turkey is expected to double. At the same time, China and Turkey have had tensions over the role of the Islamic Uighur in Xinjiang. Since Turkey is in a key position on the imperialist chessboard where Russian, European, American, Iranian ambitions are all clashing with each other, any Chinese move towards Turkey will add more explosive elements to this deeply conflicted area.

The Maritime Silk Road and its counter-moves

As part of the “One Belt - One Road” project, Iran has a specific importance. New transport corridors between Iran and China have been opened, and new port facilities in Iran are under construction.[18] At the same time, renewed US sanctions against Iran will make it possible for China to gain more influence in Iran – almost similar to the effects of the Western sanctions against Russia, which also led to increased dependence of Russia on China and thus to a globally increased weight of China.

The Chinese expansion in the Indian Ocean compels all bordering states to position themselves. On the one hand China must push its Maritime Silk Road along the coasts of the Indian Ocean up to the Iranian coast. This creates additional tensions between Pakistan and India. In Pakistan, the port of Gwadar, not far from the Iranian border, will be connected to the extreme west of China after the construction of a 500 km road connection. The port should give Chinese trade easier access to the Middle East than by sea through the Strait of Malacca (between Malaysia and Indonesia). India is protesting against this road project that crosses the part of Kashmir claimed by New Delhi. A new international airport is to be built in Gwadar.

And the Maritime Silk Project also pushes India to take counter-measures. On the one hand Iran does not want to be too dependent on China: this is why it seeks to strengthen its ties with India. India contributed to the construction of the new Iranian port of Chabahar, allowing India to avoid passing through Pakistan to reach Afghanistan. At the same time, India itself which has had special links with Russia for decades, has intensified these, despite the fact that on a military level India has also tried to diversify its arms purchases at the expense of Russia and that India is seen by the US as an important counter-weight against Chinese expansion. It has received American backing for its stronger militarisation, in particular increasing its nuclear capabilities. And together with Russia, Iran and Azerbaijan, India has been attempting for some time to establish an International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) which is to connect Mumbai to St Petersburg via Tehran and Baku/Azerbaijan.[19]

In addition India and Japan have launched the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC), trying to intensify links between Japan, Oceania, South-East Asia, India and Africa…. with the plans to build an India-Burma-Thailand motorway. As for the scramble for port facilities in the Indian Ocean, China has signed deals to set up new port facilities in Hambantota in Sri Lanka and begun the modernisation of ports in Bangladesh. Both in Pakistan and in Sri Lanka this led to spiral of new debts. The construction of the port facilities in Hambantota will give China a 99 year control over the port.

The development in Afghanistan sheds light on the main beneficiaries of the almost 40 years of war in the country.

Russia had to withdraw its troops after its occupation of Afghanistan from 1979-1989, following a 10 year- long war of attrition, which contributed to the implosion of the Soviet Union. The US-led coalition forces in Afghanistan have also experienced a real fiasco, where after more than 15 years of occupation of the country by western troops, the coalition has not been able to stabilise the country. On the contrary, in the midst of widespread terror across the country, their own troops fear for their lives wherever they go. While the western countries poured billions of dollars into Afghanistan for waging war and have stationed thousands of troops (many of whom have become traumatised), China has bought mines (for example at the price of $3.5 billion for a copper mine in Aynak) and is building a railway line connecting Logar (south of Kabul) with Torkham (a Pakistan border town) without any military mobilisation as yet. But while China has so far been spared from military attacks in Afghanistan, there is no guarantee that this will continue. [20]

The increasing Chinese influence along the “String of Pearls” in South-East Asia and the geo-strategic advance along the Maritime Silk Road will thus sharpen contradictions in this part of the Asia.

Africa: China set to challenge European domination

In addition to the expansion of Chinese influence on the Asian continent in different directions, China has also begun advancing its pawns into Africa, where Chinese boats arrived as early as 1415. At that time China did not settle in Africa. This left room for the European colonial powers, whose expansion across the world began shortly afterwards. Now, 600 years later, it is above all European influence in Africa which China is pushing back. In 2018 it is estimated that around one million Chinese live on the African continent (workers, shop and company owners). The construction of the above mentioned railway lines in Ethiopia and in Kenya and plans for more extensive railway connections highlight their long-term ambitions in Africa. A number of countries (Djibouti, Egypt, Algeria, Cape-Verde, Ghana, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and Angola) have begun buying Chinese military technology; Namibia and Ivory Coast plan to have centres facilitating the supplies for the Chinese navy. As mentioned above, we will deal with Chinese expansion into Africa in a future article.

Concluding this article, when we examine the ambitions behind the “One Belt One Road” project, we are left in no doubt that this huge undertaking is more than an economic “recovery” program. Building such a gigantic infrastructure is inseparably linked to long-term Chinese ambitions of becoming the leading power, with the goal of toppling the US. Even if nobody can predict at the moment whether this project can be implemented in view of the unpredictable factors and risks mentioned above, such an expansion is not only bound to reshape the imperialist constellations in Asia - it will also have far-reaching implications in Europe and in the other continents.

Gordon, September 2018

[1] Foreign Direct Investment

[2] Foreign Direct Investment

[4] By 2018 the railway connected China already with around 30 European freight train stations. The 3 week long railway journey is shorter but still more expensive than the maritime route.

[5] In Turkey, three Chinese state-owned companies have acquired the country's third port, Kumport, near Istanbul. 10 billion dollar investments in Bagamoyo, Tanzania, Hambantoto in Sri Lanka, major investments in Cebu and Manila are scheduled. As for industrial parks, China is building a high-tech industrial park in Minsk/Belarus , the largest ever built abroad by the Asian giant. A similar project comes out of land in Kuantan, Malaysia for steel, aluminum and palm oil.

[6] In less than 20 years, China has become Africa's leading economic partner. Their trade reached $190 billion in 2016 and is now larger than that of the continent with India, France and the United States combined, according to figures released at https://www.capital.fr/economie-politique/nouvelles-routes-de-la-soie-le...

[8] quote from Diplomatie p. 65, « Gépolitique de la Chine »

“ In current dollars, Chinese GDP represented only 1.6% of total world GDP in 1990. This ratio rose to 3.6% in 2000 and 14.8% in 2016. Strategically, the key ratio between Chinese GDP and US GDP rose from 6% in 1990 to 11.8% in 2000 and 66.2% in 2017. (...) Compared to Japan, China accounted for only a quarter of the Japanese economy in 2000, surpassed Japan in 2011 before representing 225% of Japan in 2016 and probably over 250% in 2017)”.

[9] President Harry Truman signed the Marshall Plan on April 3, 1948, granting $5 billion in aid to 16 European nations. During the four years the plan was in effect, the United States donated $17 billion (equivalent to $193.53 billion in 2017) in economic and technical assistance to help the recovery of the European countries that joined the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation. The $17 billion was in the context of a US GDP of $258 billion in 1948, and on top of $17 billion in American aid to Europe between the end of the war and the start of the Plan that is counted separately from the Marshall Plan. The Marshall Plan was replaced by the Mutual Security Plan at the end of 1951; that new plan gave away about $7 billion annually until 1961 when it was replaced by another program

[11] Diplomatie, January, 2018, p. 33

[13] https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/int/csto.htm https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collective_Security_Treaty_Organization

[16] After having relied on the logistics of Central Asian airports in the US-led war in Afghanistan, the US closed their military base in Manas (Kyrgyzstan) in 2014.

[18] The first train from China arrived at the time when US President Trump announced the cancellation of US participation in the Iran-nuclear deal in May 2018, thus making it possible for Iran to thwart parts of the US sanctions through Chinese railway connections.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace