Submitted by ICConline on

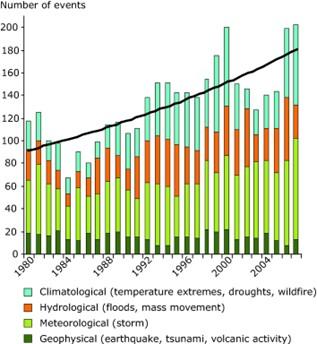

Graph shows natural disasters in Europe from 1980 to 2007 (European Environment Agency)

In a previous article[1] we condemned the recent catastrophic floods in Valencia and highlighted the crass incompetence of the bourgeoisie both to prevent and to react effectively to a disaster that it presents to us as the result of ‘the unpredictability of nature’ and ‘the impact of bad management’. The figures are frightening: more than 200 dead, more than 850,000 people directly affected, tens of thousands of damaged homes and vehicles, the collapse of transport, business and education centres, and traumatic psychological consequences for the inhabitants. In 2021, we witnessed a similar phenomenon in Germany and other Central European countries[2], with more than 240 dead, thousands injured and billions of euros worth of material damage.

The scale of these two disasters aroused the despair and anger of outraged people. Already in Germany, the media were highlighting the lack of preparation for climate change: “Deadly floods reveal shortcomings in disaster preparedness in Germany”; “while heavy rain was expected, many residents were not warned”; “deadly floods in Germany were up to nine times more likely due to climate change, and the risk will continue to increase”(CNN). But beyond the resigned observations of the bourgeoisie, the search for those to blame, the illusion of ‘solidarity’-type reconstruction and the solemn promises of governments to get involved in the fight against climate change, we need to identify the underlying causes and consequences of these disasters, those that are hidden behind the horror of the images and the negligence of the authorities.

The breakdown of capitalism leads to more disasters

These terrible floods are not just an anecdote in the succession of disasters throughout human history. From the end of the 1980s, a trend began to emerge towards the accumulation of a whole series of natural catastrophes and disasters of various kinds in the daily lives of the countries at the heart of capitalism: the chemical accidents at the Seveso factories, the nuclear disasters at Three Mile Island and Chernobyl, the deadly effects of heatwaves, the resurgence of epidemics, air crashes and road accidents, the rise of drug addiction, and so on. Until then, the capitalist system had succeeded in limiting the proliferation of these phenomena to peripheral countries, but while they continued to multiply there, they also tended to spread to the whole planet, fully affecting, like a boomerang, the major metropolises at the heart of the system.

See graph showing natural disasters in Europe from 1980 to 2007 (European Environment Agency)

At the end of the 1980s, after years of decaying capitalism, the historical situation reached an impasse: faced with the resurgence of the economic crisis, the bourgeoisie was unable to implement its ‘solution’ of mobilising for a new apocalyptic world war, because of the development of workers' struggles. The proletariat, for its part, mobilised in a series of major open struggles from the late 1960s onwards, but was unable to move towards politicising its struggle and decisively confronting the bourgeoisie. The consequence of this impasse in the balance of forces between the two antagonistic classes was an intensification of the process of social putrefaction, illustrated in particular by the collapse of the Eastern capitalist bloc and the entry into a New World Disorder[3], a terrifying dynamic, apparently less direct, but ultimately just as destructive as world war itself.

The scale of decomposition is perfectly illustrated, on a strictly ecological level[4], by manifestations ranging from the expansion of asphyxiating megalopolises and pollution of all kinds to global phenomena such as the greenhouse effect and climate change, themselves exacerbated by the multiplication of the interconnected effects of war and economic crisis. The bourgeoisie is increasingly unable to conceal its powerlessness in the face of the prospect of a chain of disasters to come.

While the capitalist system exploits the most advanced technology and resources to arm itself to the teeth, to set up instant transatlantic communications and to conduct the most complex scientific and technical research, at the same time it is suffering from the deepening of its internal contradictions and is therefore less and less able to postpone the worst consequences of these to the future and cannot prevent the effects of decades of decline from turning against it.

Referring to the floods of 2021, the Oxford Environmental Change Institute points out that “this shows the extent to which even developed countries are not immune to the impact of extreme weather conditions, which we know will worsen with climate change”. Extreme phenomena will become increasingly frequent, as shown by the recent succession of extreme droughts and floods in the Mediterranean. In the aftermath of 2021, a series of scientific surveys were commissioned to supposedly try to prevent these kinds of unexpected disasters, and the European Environment Agency asked the question: “floods in 2021, will Europe heed the warnings?” The answer is clearly no, as we saw in Valencia. In reality, capitalism is proving increasingly incapable of responding to scientific recommendations concerning the future of humanity and the planet.

On the contrary, there is even a tendency for the state to abandon the population, not just because of a lack of preparation, chaos or the deterioration of warning systems, but fundamentally because of a lack of resources and the way in which the bourgeoisie is dodging the problem, passing the hot potato of responsibility between its various regional or central factions. Already in Germany in 2021, the criticism was that “communities should decide how to react. In the German political system, the regional states are responsible for emergency efforts” (BBC News). In Spain, we have seen a similar spectacle, if not worse. In the face of this growing trend towards abandonment, “what gave hope was the arrival of volunteers from all over Germany at the scene of the tragedy, clearing away the mud, talking to those affected... and donations reached record levels” (DW News). Similarly, the disaster in Spain generated a similar surge of popular solidarity, reflecting the social nature of human beings. But does this kind of social impulse represent hope for the future, does it form the basis of the struggle for a society that will overcome capitalism?

Before delving any further into this question, we should note that, beyond the trivialisation of these disasters and their normalisation, the idea is increasingly propagated of ‘the need to adapt to inescapable changes’, so as to inculcate the idea that it is impossible to anticipate and therefore that we will have to ‘make do’, hoping to contain the most destructive effects, thus stimulating fatalism and despair, the every-man-for-himself attitude and individual resourcefulness in the face of a system that declares itself incapable of reversing the trend. In fact, the world's climate summits have gone from being totally hollow commitments to open shams! The last COP 29, marked by the absence of a large number of world leaders, produced results that were described as disappointing by the bourgeois press itself: “a shameful agreement” (Greenpeace); “a complete waste of time”’ (EuroNews). For Nature magazine, the funds allocated will not convince anyone, and the agreement does not even anticipate the impact of the next ‘Trump scenario’[5]; Cambridge researchers present at the COP confided: “I didn't speak to a single scientist who thought that the 1.5°C limit was still achievable with current resources”.

Where is the hope for the future?

In Spain, the spontaneous reaction of the population to the disaster gave rise to a wave of volunteers and an outpouring of generosity to help those affected and, faced with the inaction and incompetence of the state, even generated slogans such as “only the people can save the people”’. This reaction was shamelessly exploited by various factions of the bourgeoisie, from its extreme right to its extreme left. The far-left groups have shared the work with the left parties by subtly redirecting workers' thinking towards the bourgeois terrain. They never present us with a serious analysis of the evolution and nature of capitalism, but offer workers all sorts of false alternatives based on ‘popular management’ of the capitalist system. Groups like ‘Izquierda Revolucionaria’ in Spain or the German branch of the Committee for a Workers’ International, or the World Socialist Website, spit fire at the “irresponsibility and criminal inaction of politicians and authorities” and first tell us that “capitalism is responsible” only to claim that “it is not the establishment, but the people themselves who have organised solidarity and hospitality and even part of the hospitality. Donations, people, services and rescue workers... a hopeful solidarity ‘from below’ that needs to be democratised and coordinated effectively”. A caricature of the ideology according to which spontaneous solidarity in the face of catastrophe is a proletarian alternative to the negligence of capitalism is defended, for example, by the Trotskyists of ‘Left Voice’ (Révolution Permanente in France) who say that it can provoke a kind of ‘catastrophe communism’, where “people free themselves from the capitalists and start to rebuild society in a collaborative way ... when I feel climate despair, I think of the prospect of joining with other people around the world to fight the catastrophe”.

In Valencia, we saw how all the solidarity, anger, indignation and despair aroused by the disaster were channelled into national unity campaigns such as the joint mourning rallies with businessmen at company gates in ‘support for Valencia’ or ‘for the people of Valencia, proud of their solidarity’. The anarchists who normally call for ‘neighbourhood alternatives’ and self-management have embarked on the adventure of ‘local solidarity networks, for the self-organisation and empowerment of the people’. And the provocation of the arrival of the authorities was met with a shower of mud and insults.

However, there was no hint of a class approach, no protest against the pressure on workers to continue working, or against the loss of wages, unemployment subsidies or housing benefit. As there were no assemblies or discussions to reflect on the root causes of the disaster, the leftists and the unions had no trouble channelling some of the anger, while some of the inhabitants lost their way in pure disorientation, in conflicts between bourgeois parties, or even in populism against the inept political elites, ‘insensitive to the suffering of the people’.

We should have no illusions about the impact of these immediate reactions! When the reflexes of social survival do not find expression on a class terrain, they are immediately put to good use by the bourgeoisie to disarm the proletariat, preventing it from developing its own class response! This kind of spontaneous indignation, despair and rage within society in the face of destruction, fundamentally expresses impotence, frustration and a lack of perspective in the face of the rotting of society. The effects of the decomposition of capitalism, in themselves, do not constitute a favourable basis for a reaction of the proletariat as a class against capitalism, as the leftists would have us believe. They oppose and replace the class struggle of the proletariat with the shapeless magma that is the ‘people’, thus condemning the workers to be diluted into the dominated and powerless mass of ‘those below’.

The acceleration of the decomposition of capitalism will inevitably lead to a multiplication of increasingly terrible catastrophes, in the face of which states will show themselves to be increasingly incompetent and indifferent. The bourgeoisie will ideologically exploit both the effects of the decomposition of its system and ‘spontaneous reactions of solidarity’ to rally the population behind the defence of the state, with supposed purges of the corrupt or promises of improved efficiency in its management. But the exploitation of human solidarity by the ruling class (from voluntary sacrifices at work to humanitarian campaigns to give credibility to the system) does not give rise to any flame of hope for the future. Only the working class, through its struggle against the attacks on its living conditions, and the search for its extension and unity, its politicisation, represents the hope of overthrowing this rotten society.

Opero, 12 January 2025

[1] Floods in Valencia: capitalism is an unfolding catastrophe, ICC Online. At the time of writing, gigantic fires are raging in the Los Angeles region in the United States. The negligence and growing inability of the bourgeoisie to deal with the disasters caused by its system has been confirmed once again.

[2] Capitalism is dragging humanity towards a planet-wide catastrophe, July 2021, ICC Online

[3] The ‘New World Order’ is an expression coined by Bush Senior during the invasion of Kuwait, referring to a new era in which the United States was supposed to ensure order as the world's policeman.

[4] Sequía en España: el capitalismo no puede mitigar, ni adaptarse, solo destruir, CCI Online, March 2024

[5] The ‘Trump scenario’: the new Trump administration intends to dismiss any talk of climate change, implementing a ‘drill baby drill’ policy while withdrawing from all international treaties combating global warming. Trump's response to the catastrophic fires in Los Angeles sets the tone: Trump did not blame the drying up of forests due to climate change, but the alleged refusal of the governor of California to release water reserves in the region just to protect what Trump calls a ‘worthless fish’, the smelt.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace