Submitted by International Review on

Understanding the Decadence of Capitalism, Part 6

In two previous articles, we demonstrated that all modes of production are regulated by an ascendant and a decadent cycle (International Review no. 55), and that today we are living in the heart of capitalism’s decadence (International Review no. 54). The present article aims to give a better description of the elements that have made it possible for capitalism to survive throughout its decadence, and in particular to provide a basis for understanding the rates of growth in the period following 1945 (the highest in capitalism’s history). Above all, we will demonstrate that this momentary upsurge is the product of a doped growth, which is nothing other than the desperate struggle of a system in its death-throes. The means that have been used to achieve it (massive debts, state intervention, growing military production, unproductive expenditure, etc) are wearing out, opening the way to an unprecedented crisis.

THE FUNDAMENTAL CONTRADICTION OF CAPITALISM

“The decisive question in the production process is the following: what is the relationship between those who work and their means of production?” (Rosa Luxemburg, Introduction to Political Economy). Under capitalism, the relationship linking workers to the means of production is that of wage labour. This is the fundamental social relation of production that both gives capitalism its dynamic, and contains its insurmountable contradictions[1]. It is a dynamic relationship, in the sense that the system must continuously grow, accumulate, expand, and push wage exploitation to the limit, spurred on by the rate of profit’s tendency to decline, and by its equalisation as a result of the laws of value and of competition. It is a contradictory relationship in the sense that the very mechanism for producing surplus-value produces more value than it is able to distribute, surplus-value being the difference between the production value of the commodity produced, and the value of the commodity produced, and the value of the commodity labour-power, in other words, wages. By generalising wage-labour, capitalism limits its own outlets, constantly forcing the system to find buyers outside its own sphere of capital and labour.

“...The more capitalist production develops, the more it is forced to produce on a scale which has nothing to do with immediate demand, but depends on a constant extension of the world market... Ricardo does not see that the commodity must necessarily be transformed into money. The demand from workers cannot suffice for this, since profit comes precisely from the fact that workers’ demand is less than the value of what they produce, and is all the greater when this demand is relatively smaller. The demand of capitalists for each other’s goods is not enough either... To say that in the end the capitalists only have to exchange and consume commodities amongst themselves is to forget the nature of capitalist production, and that the point is to transform capital into value... Over-production springs precisely from the fact that the mass of the people can never consume more than the average quantity of staple goods, and that their consumption does not increase at the same rhythm as the productivity of labour... The simple relationship between capitalist and wage labourer implies:

1) That the majority of producers (the workers) are not consumers, or buyers, of a substantial part of what they produce;

2) That the majority of producers, of workers, can not consume an equivalent of their product as long as they produce more than this equivalent, in other words surplus-value. They must constantly be over-producers, producing beyond their own needs in order to be consumers or buyers... The special condition of over-production is the general law of production under capital: to produce according to the productive forces, i.e.l according to the possibility of exploiting the greatest possible mass of labour with a given mass of capital, without taking account of the existing limits of the market or of solvent demand...” (Marx, Capital Book IV, Vol II and Book III, Vol I).

Marx clearly showed, on the one hand, the inevitability of capitalism’s race to increase the mass of surplus-value in order to compensate the fall in the rate of profit (dynamic), and on the other the obstacle before it; the outbreak of crises due to the shrinking of the market where its production can be sold (contradiction) long before there appears any lack of surplus-value due to the fall in the rate of profit:

“So, as production increases, so the need for markets also increases. The more powerful and more costly means of production that [the capitalist] has created allow him to sell his commodities more cheaply, but at the same time they force him to sell more commodities, to conquer an infinitely greater market for his commodities... Crises become more and more frequent and more and more violent because, as the mass of products and so the need for larger markets grows, the world market shrinks more and more, and there remain fewer and fewer markets to exploit, since each previous crisis has subjected to world trade a market which had up to then not been conquered, or had been exploited only superficially,” (Marx, Wage Labour and Capital).

This analysis was systematised and more fully developed by Rosa Luxemburg, who came to the conclusion that since the totality of the surplus-value produced by global social capital cannot, by its very nature, be realised within the purely capitalist sphere, capitalism’s growth is dependent on the continuous conquest of pre-capitalist markets; the exhaustion of the markets relative to the needs of accumulation would topple the system into its decadent phase:

‘Through this process, capitalism prepares its own collapse twice over: on the one hand, by spreading at the expense of non-capitalist modes of production, it brings forward the moment when the whole of humanity will be composed only of capitalists and proletarians, and where further expansion, and therefore accumulation, will become impossible. On the other hand, as it advances it exasperates class antagonism and international economic and political anarchy to such a point that it provokes the international proletariat’s rebellion against its domination long before the evolution of the economy has reached its final conclusion: capitalist production’s absolute and exclusive world domination... Present-day imperialism... is the last stage in [capitalism’s] historic process: the period of heightened and generalised world competition between capitalist states for the last remnants of the planet’s of the planet’s non-capitalist territories,” (The Accumulation of Capital).

Apart from her analysis of the inseparable link between capitalist relations of production and imperialism, which demonstrated that the system cannot survive without expanding, and that it is therefore imperialist by nature, Rosa Luxemburg’s fundamental contribution lies in providing the analytical tools for understanding how, when and why the system entered its period of decadence. Rosa answered this question with the outbreak of the 1914-18 war, considering that the worldwide inter-imperialist conflict opened the period where capitalism becomes a hindrance for the development of the productive forces:

“The necessity of socialism is fully justified as soon as the domination of the bourgeois class no longer encourages historical progress, and becomes a hindrance and a danger for society’s further evolution. As far as the capitalist order is concerned, this is precisely what the present war has revealed” (Rosa Luxemburg, quoted in Rosa Luxemburg: journaliste, polemiste, revolutionnaire, by G. Badia).

Whatever the various “economic” explanations put forward, this analysis was shared by the whole revolutionary movement.

A clear grasp of this insoluble contradiction of capital provides a reference point for understanding the how the system has survived during its decadence. Capitalism’s economic history since 1914 is the history of the development of palliatives for the bottleneck created by the world market’s inadequacy. Only through such an understanding can we put capitalism’s occasional “good performance” (such as post-1945 growth rates) in its place. Our critics (see International Review, nos. 54 and 55) are dazzled by the figures for these growth rates, but this blinds them to their NATURE. They thus depart from the marxist method, which aims to bring out the real nature of things that lies hidden behind their existence. This real nature is what we intend to demonstrate here [2].

WHEN THE REALISATION OF SURPLUS-VALUE BECOMES MORE IMPORTANT THAN ITS PRODUCTION

During the ascendant phase, demand in general outstrips supply; the price of commodities is determined by the highest production costs, which are those of the least developed sectors and countries. This makes it possible for the latter to make profits, which allow a real accumulation, while the most developed countries are able to realise super-profits. In decadence, the reverse is true; on the whole supply is greater than demand and prices are determined by the lowest production costs. As a result, the sectors and countries with the highest production costs are forced to sell at a reduced profit or even at a loss, or to cheat with the law of value to survive (see below). This reduces their rate of accumulation to an extremely low level. Even the bourgeois economists have, in their own language (that of sale price and cost price) observed this inversion:

“We have been struck by today’s inversion of the relation between cost price and sale price... in the long term, the cost price still keeps its role... But whereas previously, the principal was that the sale price could always be fixed above the cost price, today it usually appears to be subjected to the market price. In these conditions, when it is no longer production but sale that is essential, when competition becomes increasingly bitter, companies take the sale price as a starting point, and progressively work back to the cost price... in order to sell, companies tend today to consider first and foremost the market, and therefore the sale price... This is so true that we now-a-days often come up against the paradox that it is less and less the cost price that determines the sale price, and more and more the reverse. The problem is: either give up producing, or produce below the market price” (J. Fourastier and B. Bazil, Pourquoi les prix baissent).

A spectacular indication of this phenomenon appears in the wildly disproportionate proportion of distribution and marketing in the product’s final cost. These functions are carried out by commercial capital, which takes a share in the overall division of surplus-value, so that its expenses are included in the cost of production. In the ascendant phase, as long as commercial capital ensured the increase of the mass of surplus-value and of the annual rate of profit by reducing the period of commodity circulation and speeding up the circulation of capital, it also contributed to the general decline in prices characteristic of the period (see graph 4). In the decadent phase, this role changes. As the productive forces come up against the limits of the market, the role of commercial capital is less to increase the mass of surplus-value than to ensure its realisation. This is expressed in capitalism’s concrete reality, on the one hand by a growth in the number of people employed in distribution and in general by a decline in the number of surplus-value producers relative to other workers, and on the other by the growth of commercial margins in the final surplus-value. It is estimated that in the major capitalist countries today, distribution costs account for between 50% and 70% of commodity prices. Investment in the parasitic sectors of commercial capital (marketing, sponsoring, lobbying, etc.) is gaining increasing weight relative to investment in the production of surplus-value. This simply comes down to a destruction of productive capital, which in turn reveals the system’s increasingly parasitic nature.

1. CREDIT

“The system of credit thus accelerates the material development of the productive forces and the constitution of the world market; the historic task of capitalist production is precisely to push these two factors to a certain degree of development, as the material basis for the new form of production. Credit accelerates both the violent explosions of this contradiction – crises – and as a result the development of those elements which dissolve the old mode of production” (Marx, Capital, Book III).

In the ascendant phase, credit was a powerful means of accelerating capitalism’s development by shortening the cycle of capital accumulation. Credit, which is an advance against the realisation of a commodity, could complete its cycle thanks to the possibility of penetrating new extra-capitalist markets. In decadence, this outcome is less and less possible; credit thus becomes a palliative for capital’s increasing inability to realise the totality of the surplus-value produced. The accumulation that credit makes temporarily possible only develops an insoluble abscess that inevitably comes to a head in generalised inter-imperialist war.

Credit has never constituted a solvent demand in itself, and still less in decadence as Communisme ou Civilisation (CoC) would have us say: “Credit has now found a place among the reasons which allow capital to accumulate; one might as well say that the capitalist class is able to realise surplus-value thanks to a solvent demand coming from the capitalist class. While this argument does not appear in the ICC’s pamphlet on the Decadence of Capitalism, it has now become a part of the panoply of all the initiates to the sect. They now admit what was previously fiercely denied: the possibility of realising the surplus-value destined for accumulation: (CoC no. 22) [3]. Credit is an advance on the realisation of surplus-value, and so makes it possible to accelerate the closure of the complete cycle of capitalist reproduction. According to Marx, this cycle – as is too often forgotten – includes both production AND the realisation of the commodity produced. What changes between the ascendant and the decadent phases of capitalism, are the conditions within which credit operates. The worldwide saturation of the market makes the recovery of invested capital increasingly slow, and indeed decreasingly possible. This is why capital more and more lives on a mountain of debts, which are taking on astronomical proportions. Credit thus makes it possible to keep up the fiction of an enlarged accumulation, and to put off the final day of reckoning, when capital has to pay up. Since it is unable to do so, capital is pushed inexorably towards trade wars, and then to inter-imperialist war. War is the only “solution” for the crises of over-production in decadence (see International Review no. 54). The figures in Table 1 and Graph 1 illustrate this phenomenon.

Concretely, the figures in Table 1 show that the USA lives on 2.5 years of credits, Germany on 1 year. If these credits were ever to be repaid, the workers of these countries would have to work respectively 2.5 and 1 years for nothing. These figures also show that debt is growing faster than GNP, indicating that over time economic development is more and more taking place through credit.

These two examples are no exception, but illustrate the world indebtedness of capitalism. This is extremely hazardous to calculate, above all due to the lack of any reliable statistics, but we may estimate that debt is between 1.5 and 2 times world GNP. Between 1974 and 1984, world debt grew at a rate of about 11%, while the growth rate of world GNP hovered at about 3.5%!

Table 1. The Evolution of Capitalism’s Debt

|

|

State and Private Debts |

(as % GNP) |

Household Debts (as % disposable income) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

West Germany |

USA |

USA |

1946 |

- |

- |

19.6% |

1950 |

22% |

- |

- |

1955 |

39% |

166% |

46.1% |

1960 |

47% |

172% |

- |

1965 |

67% |

181% |

- |

1969 |

- |

200% |

61.8% |

1970 |

75% |

- |

- |

1973 |

- |

197% |

71.8% |

1974 |

- |

199% |

93% |

1975 |

84% |

- |

- |

1979 |

100% |

- |

- |

1980 |

250% |

- |

- |

Sources: Economic Report of the President (01/1970)

Survey of Current Business (07/1975)

Monthly Review (vol. 22, no.4, 09/1970, p.6)

Statistical Abstract of the United States (1973).

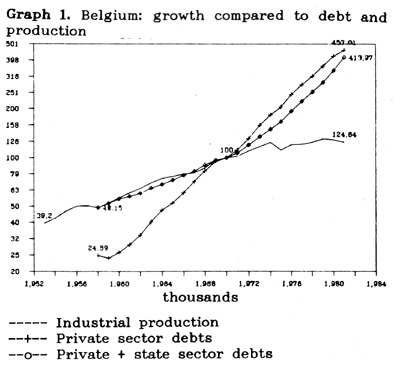

Source: Bulletin de l’IRES 1982, no. 80 (the left hand scale is an index of the evolution of the two indicators which have been given a value of 100 in 1970 for purposes of comparison).

Graph no.1 illustrates the evolution of growth and debt in most countries. Debts are clearly growing faster than industrial output. Whereas previously, growth was increasingly dependent on credit (1958-74: production = 6.01%, credit = 13.26%), nowadays the mere continuation of stagnation depends on credit (1974-81: production = 0.15%, credit = 14.08%).

Since the beginning of the crisis, each economic recovery has been sustained by an ever-greater mass of credit. The recovery of 1975-79 was stimulated by credits accorded the ‘Third World’ and so-called ‘socialist’ countries, that of 1983 was entirely sustained by a growth of borrowing on the part of the American authorities (essentially devoted to military spending), and of the great North American trusts (devoted to company mergers, therefore unproductive). CoC does not understand this process at all, and completely under-estimates the expansion of credit as capitalism’s mode of survival in decadence.

EXTRA-CAPITALIST MARKETS

We have already seen (International Review no. 54) that the decadence of capitalism is characterised not by the disappearance of extra-capitalist markets, but by their inadequacy relative to capitalism’s needs for expanded accumulation. This means that the extra-capitalist markets are no longer sufficient to realise the whole of the surplus-value produced by capitalism, and destined for reinvestment. Spurred on by an increasingly limited basis for accumulation, decadent capitalism tried to exploit as effectively as possible the outlet that the survival of these markets provides, in three ways.

Firstly, through an accelerated and planned integration of the surviving sectors of mercantile economy within the developed countries.

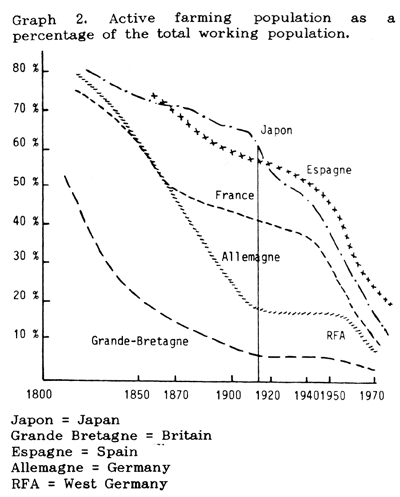

Graph no. 2 shows that whereas in some countries, the integration of the mercantile farm economy within capitalist social relations of production had already been completed by 1914, in others (France, Spain, Japan, etc) it continued during decadence, and accelerated after 1945.

Up until World War II, labour productivity increased more slowly in agriculture than in industry as a result of a slower development in the division of labour, due amongst other things to the still important weight of land rent, which diverted part of the capital needed for mechanisation. Following World War II, labour productivity grew faster in agriculture than in industry. This took the form of a policy of using all possible means to ruin subsistence family farms, still tied to small-scale mercantile production, so as to transform them into purely capitalist business. This is the process of the industrialisation of agriculture.

Spurred on by the search for new markets, the period of decadence is characterised by the improved exploitation of the surviving extra-capitalist markets.

On the one hand, improved techniques, improved communications, and falling transport costs facilitated the penetration – both in degree and extent – and destruction of the mercantile economy in the extra-capitalist sphere.

On the other hand, the development of policies of ‘decolonisation’ relieved the metropoles of a costly burden, and allowed them to improve returns on their capital and to increase sales to their old colonies (paid for by the super-exploitation of the indigenous populations). A large part of these sales were made up of armaments, the first and absolute need in building local state power.

The context in which capitalism developed in its ascendant phase made possible a unification of the conditions of production (technical and social conditions, the average productivity of labour, etc). Decadence, by contrast, has increased the inequalities in development between the developed and under-developed countries (see International Review nos. 23 and 54).

Whereas in ascendancy, the profits extracted from the colonies (sales, loans, investments) were greater than those resulting from unequal exchange [4], in decadence the reverse takes place. The evolution of terms of exchange over a long period indicates this tendency. They have greatly deteriorated for the so-called ‘Third World’ countries since the second decade of this century.

Graph 3 below illustrates changes in the terms of trade between 1810 and 1970 for "Third World" countries, i.e. the ratio between the price of raw products exported and the price of industrial products imported. The scale expresses a price ratio (x 100), which means that when this index is greater than 100, it is favourable to "Third World" countries, and vice versa when it is less than 100. It was during the second decade of this century that the curve passed the pivotal index of 100 and began to fall, interrupted only by the 1939-45 war and the Korean war (strong demand for basic products in a context of scarcity).

STATE CAPITALISM

We have seen already (International Review no. 54) that the development of state capitalism is closely linked to capitalism’s decadence [5]. State capitalism is a worldwide policy forced on the system in every domain of social, political and economic life. It helps to attenuate capitalism’s insurmountable contradictions: at the social level by a better control of a working class which is now sufficiently developed to be a real danger for the bourgeoisie; at the political level, by dominating the increasing tension between bourgeois factions; at the economic level by soothing an accumulation of explosive contradictions. At this latter level, which is the one that concerns us here, the state intervenes by means of a series of mechanisms:

Cheating the law of value

We have seen that in decadence an increasingly important share of production escapes the strict determination of the law of value (International Review no. 54). The purpose of this process is to keep alive activities which would not otherwise have survived the law of value’s merciless verdict. Capitalism thus manages for a while, but only for a while, to avoid the consequences of the market’s Caudine Forks.

Permanent inflation is one means to meet this end. It is, moreover, a typical phenomenon of a mode of production’s decadence [6].

Whereas in the ascendant period the overall tendency is for prices to remain stable or fall, in decadence this tendency is reversed. 1914 inaugurates the phase of permanent inflation.

After remaining stable for a century, prices in France exploded following the First World War, and even more after the Second; they have increased 1000-fold between 1914 and 1982.

Source: INSEE.

If a periodic fall and readjustment of prices to exchange values (price of production) is artificially prevented by swelling credit and inflation, then a whole series of companies whose labour productivity has fallen below the average in their branch can nonetheless escape the devalorisation of their capital, and bankruptcy. But in the long run, this can only increase the imbalance between productive capacity and solvent demand. The crisis is delayed, only to return still further amplified. Historically, in the developed countries, inflation first appeared with state spending tied to armaments and war. Later on, the development of credit and unproductive expenditure of all kinds were added to arms spending, and took its place as the major cause of inflation.

The bourgeoisie has adopted a series of anti-cyclical policies. Armed with the experience of the 1929 crisis, which was considerably aggravated by isolationism, the ruling class has got rid of its remaining pre-1914 free-trade delusions. The 1930’s, and still more the period after 1945 with the advent of Keynesianism, were marked by a string of concerted state capitalist policies. It would be impossible to list them all here, but they all have the same aim in view: to get control over fluctuations in the economy, and artificially support demand.

The level of state intervention in the economy has grown. This point has already been dealt with at length in previous issues of the International Review; here we will deal only with an aspect which has so far only been touched on: the state’s intervention in the social domain, and its implications for the economy.

During capitalism’s ascendant phase, increasing wages, the reduction in the working day, and improved working conditions were “concessions wrested from capital through bitter struggle... the English law on the 10 hour working day, is in fact the result of a long and stubborn civil war between the capitalist class and the working class” (Marx, Capital). In decadence, the bourgeoisie’s concessions to the working class following the revolutionary movements of 1917-23 represented, for the first time, measures taken to calm (8-hour day, universal suffrage, social insurance etc) and to control (labour contracts, trade union rights, workers’ commissions, etc.) a social movement whose aim was no longer to gain lasting reforms within the system, but to seize power. These last measures to be taken as a spin-off from the struggle highlight the fact that in capitalism’s decadence, the state, with the help of the trade unions, organises, controls and plans social measures in order to ward off the proletarian threat. This is marked by the swelling of state spending devoted to the social domain (indirect wages subtracted from the overall mass of wages).

Table 2. State Social Expenditure

(as a % of GNP)

|

|

|

Ger |

Fra |

GB |

US |

|

ASCENDANCE |

1910 |

3.0% |

- |

3.7% |

- |

|

|

1912 |

- |

1.3% |

- |

- |

|

DECADENCE |

1920 |

20.4% |

2.2% |

6.3% |

- |

|

|

1922 |

- |

- |

- |

3.1% |

|

|

1950 |

27.4% |

8.3% |

16.0% |

7.4% |

|

|

1970 |

- |

- |

- |

13.7% |

|

|

1978 |

32.0% |

- |

26.5% |

- |

|

|

1980 |

- |

10.3% |

- |

- |

Sources: Ch. André & R. Delorme, op. cit. in International review no. 54.

In France, the state took a whole series of social measures in a period of social calm: medical insurance in 1928-30, free education in 1930, family allowances in 1932; in Germany, medical insurance is extended to office and farm workers, help given to the unemployed in 1927. The present system of social security in the developed countries was conceived, discussed and planned during and just after World War II [7]: in France in 1946, in Germany in 1954-57 (1951 joint management law), etc.

All these measures are aimed primarily at a better social and political control of the working class, and at increasing its dependence on the state and the trade unions (indirect wages). But on the economic level, they had a secondary effect: to attenuate the fluctuations of demand in Sector II (consumer goods), where over-production first appears.

The establishment of income relief, programmed wage increases [8], and the development of so-called consumer credit are all part of the same mechanism.

ARMS, WAR, RECONSTRUCTION

In the period of capitalist decadence, wars and military production no longer have any function in capitalism’s overall development. They are neither areas for the accumulation of capital, nor moments in the political unification of the bourgeoisie (as with Germany after the 1871 Franco-Prussian war: see International Review nos. 51, 52, 53).

Wars are the highest expression of the crisis and decadence of capitalism. A Contre Courant (ACC) refuses to see this. For this ‘group’, wars have an economic function in the devalorisation of capital due to the destruction they cause, just as they express the increasing severity of crises in a constantly developing capitalism. Wars therefore do not indicate any qualitative difference between capitalism’s ascendant and decadent periods: “At this level, we would like to put into perspective even the notion of world war... All wars under capitalism thus have an essentially international content... What changes is not the invariant world content (whether the decadentists like it or not) but its extent and depth, which is constantly more truly worldwide and catastrophic” (A Contre Courant no. 1). ACC gives two examples to support its thesis: the period of the Napoleonic wars (1795-1815), and the still local nature (sic!) of the First World War relative to the Second. These two examples prove nothing at all. The Napoleonic wars were fought at the watershed between two modes of production; they are in fact the last wars of the Ancient Regime (decadence of feudalism), and cannot be taken as characteristic of wars under capitalism. Although Napoleon’s economic measures encouraged the development of capitalism, on the political level he engaged in a military campaign in the best tradition of the Ancient Regime. The bourgeoisie had no doubts about this when, after supporting him for a while, it abandoned him, finding his campaigns too expensive and his continental blockade a hindrance to its development. As for the second example, it requires either extraordinary nerve, or no less extraordinary ignorance to suggest it. The question is not the comparison of the First World War with the Second. but the comparison of both with the wars of the previous century – a comparison which ACC takes care not to make. Were they to do so, the conclusion is so obvious that no one could miss it.

After the insanity of the Ancient Regime, war was limited and adapted to capitalism’s needs for world conquest, as we have explained at some length in the International Review no. 54, only to return once again to complete irrationality in the capitalist system’s decadence. Given the deepening contradictions of capital, the Second World War was inevitably more widespread and destructive than the First, but their main characteristics are identical, and opposite to the wars of the previous century.

As for the explanation of war’s economic function through the devalorisation of capital (rise in the rate of profit – PV/CC+CV – thanks to the destruction of constant capital), it collapses under close examination. Firstly, because war also wipes out workers (CV), and secondly because the increase in capital’s organic composition also continues during war. The momentary growth in the rate of profit in the immediate post-war period is due on the one hand to the defeat and super-exploitation of the working class, and on the other to the increase in relative surplus-value thanks to the development of labour productivity.

At the end of the war, capitalism is still faced with the need to sell the whole of its production. What has changed, however, is first, the temporary decrease in the mass of surplus-value to be reinvested that has to be realised (due to the destruction caused by war), and second the decongestion of the market through the elimination of competitors (the USA grabbed most of their colonial markets from the old European metropoles).

As for arms production, it is primarily motivated by the need to survive in an environment of inter-imperialist competition, no matter what the cost. Only afterwards does it play an economic role. Although at the level of global capital, arms production constitutes a sterilisation of capital and adds nothing to the balance-sheet at the end of a production cycle, it does allow capital to spread out its contradictions in both time and space. In time, because arms production temporarily keeps alive the fiction of continued accumulation, and in space because by constantly stirring up localised wars and by selling a large part of the arms produced to the ‘Third World’, capital carries out a transfer of value from the latter to the more developed countries [9].

THE EXHAUSTION OF PALLIATIVE MEASURES

The measures which we have described above, and which were already put into partial use after the 1929 crisis without being able to resolve it (New Deal, Popular Front, De Man plan, etc.) in order to delay the deadline of capitalism’s fundamental contradiction, have already been extensively used throughout the post-war period up to the end of the 1960’s. Today, they are exhausted, and the history of the last 20 years is the history of their growing ineffectiveness.

The pursuit of military growth remains a necessity (because it is pushed by growing imperialist needs), but it no longer provides even a temporary relief for the problems of the economy. The massive cost of arms production is now sapping productive capital directly. This is why today, its growth is slowing down (except in the USA, where arms spending grew by 2.3% p.a. in the period 1976-80 and 4.6% in 1980-86), and why the ‘Third World’s’ share in arms purchases is falling, even though more and more military spending is hidden, in particular under the heading of ‘research’. Nonetheless, world military spending continues to rise each year (by 3.2% during 1980-85), at a faster rate than world GNP (2.4%).

The massive use of credit has reached the point where it provokes serious financial tremors (e.g. October 1987). Capitalism no longer has any choice but to walk a knife-edge between the danger of a return to hyper-inflation (credit getting out of control) and recession (due to the increase in interest rates to hold back credit). With the generalisation of the capitalist mode of production, production is increasingly separated from the market; the realisation of a commodity’s value, and so of surplus-value, becomes more complicated. It is increasingly difficult for the producer to know whether his commodities will find a real outlet, a “final consumer”. By allowing production to expand without any relation to the market’s ability to absorb it, credit puts off the outbreak of crises, but aggravates the imbalance in the system, which means that when the crisis does break out, it does so more violently.

Capitalism is less and less able to sustain inflationist policies that artificially support economic activity. Such a policy presupposes high interest rates (since once inflation has been deducted there is not much interest left on what has been lent). But high interest rates imply a high rate of profit in the real economy (as a general rule, interest rates must be lower than the average rate of profit). This however is more and more impossible, as the crisis of over-production and lack of sales lower the profitability of invested capital, so that it no longer produces a rate of profit sufficient to pay bank charges. This dilemma was concretised in October 1987 by the stock-market panic.

The extra-capitalist markets are all over-exploited, under immense pressure, and are quite incapable of providing a way out.

Today, the development of unproductive sectors has reached such a point that it makes things worse rather than alleviating them. The time has therefore come for the reduction of overhead expenses.

Already, the palliatives used since 1948 were not based on a healthy foundation, but their exhaustion today creates an economic dead-end of unprecedented gravity. Today, the only possible policy is a head-on attack on the working class, an attack which is carried out with zeal by every government, whether right or left, East or West. However, this austerity, thanks to which the working class pays dearly for the crisis in the name of each national capital’s “competitiveness”, provides no ‘solution’ to the overall crisis; on the contrary, it merely reduces solvent demand still further.

CONCLUSIONS

We have considered the different elements that explain capitalism’s survival, not from any academic concern, but as militants. What concerns us is to understand better the conditions for the development of the class struggle, by placing it in the only valid and coherent framework – the decadence of capitalism – by coming to grips with the different measures introduced by state capitalism, and by recognising the urgency and the dangers of the present situation due to the exhaustion of all palliatives to capitalism’s crisis (see International Review nos. 23, 26, 27, 31).

Marx did not wait until he had finished Capital before joining the class struggle. Rosa Luxemburg and Lenin did not wait to agree on the economic analysis of imperialism before taking position on the necessity of founding a new International, of fighting the war by revolution, etc. Moreover, behind their disagreements (Lenin explained imperialism by the falling rate of profit and monopoly capitalism, Luxemburg by the saturation of the market), lay a profound agreement on all the crucial questions of the class struggle, and especially the recognition of the historical bankruptcy of the capitalist mode of production that put the socialist revolution on the agenda:

“From all that has been said above about imperialism, it follows that we must characterise it as capitalism in transition, or more correctly as moribund capitalism... parasitism and putrefaction characterise capitalism’s highest historical phase, ie imperialism... Imperialism is the prelude to the social revolution of the proletariat. Since 1917, this has been confirmed on a world scale” (Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism). If these two great marxists were so violently attacked for their economic analysis, it was not for the economic analyses as such, but for their political positions. In the same way, the present attack on the ICC over economic questions in reality hides a refusal of militant commitment, a councilist conception of the role of revolutionaries, a non-recognition of the present historic course towards class confrontations and a lack of conviction in the historical bankruptcy of the capitalist mode of production.

C.McL

[1] This is why Marx was always very clear on the fact that to go beyond capitalism to the creation of socialism presupposes the abolition of wage labour: “Instead of the conservative motto ‘A fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work!’ [the workers] ought to inscribe on their banner the revolutionary watchword, ‘Abolition of the wages system!’ ... for the final emancipation of the working class, that is to say the ultimate abolition of the wages system” (Marx, Wages, Price and Profit).

[2] We do not claim here to give a detailed explanation of capitalism’s economic mechanisms and history since 1914, but simply to put forward the major elements which have allowed it to survive, concentrating on the means it has used to put off the day of reckoning of its fundamental contradiction.

[3] Here we should point out that, apart from a few ‘legitimate’, if academic, questions, this pamphlet of criticism is nothing but a series of deformations based on the principle that “he who wants to kill his dog first claims it has rabies”.

[4] The law of value regulates exchange on the basis of equivalent amounts of labour. But given the national framework of capitalist social relations of production and the increase during decadence of national differences in the conditions of production (labour productivity and intensity, organic composition of capital, wages, rates of surplus-value, etc), the equalisation of profit rates which forms the price of production takes place essentially in the national framework. There thus exist different prices for the same commodity in different countries. This means that in international trade, the product of one day’s labour of a more developed nation will be exchanged for that of one that is less developed or where wages are lower... Countries that export finished goods can sell their commodities above their price of production, while remaining below the price of production of the importing country. They thus, realise a super-profit by transfer of values. For example: in 1974 a quintal (100 kilos) of US wheat cost 4 hours wages of a labourer in the US, but 16 hours in France due to the greater productivity of labour in the US. American agri-industry could thus sell its wheat in France above the price of production (4 hours), while still remaining more competitive that French wheat (16 hours) – which explains the EEC’s formidable protection of its agricultural market, and the incessant quarrels over this question.

[5] For the EFICC, this is no longer true. The development of state capitalism is explained by the transition from the formal to the real domination of capital. Now if this were the case, we should be able to see statistically a continuous progression of the state’s share in the economy, since this transition took place over a long period, and moreover we should see it begin during the ascendant period. This is clearly not the case at all. The statistics that we have published show a clear break in 1914. During the ascendant phase, the state’s share in the economy is small and constant (oscillating around 12%), whereas during decadence, it grows to the point where today it averages about 50% of GNP. This confirms our thesis of the indissoluble link between decadence and the development of state capitalism’s, and categorically disproves that of the EFICC.

[6] After this series of articles, only someone as blind as our critics could fail to see the clear break in capitalism’s mode of existence that is represented by the First World War. All the long-term statistical series that we have published in this article demonstrate this rupture: world industrial production, world trade, prices, state intervention, terms of exchange and armaments. Only the analysis of decadence and its explanation by the worldwide saturation of the market makes this rupture comprehensible.

[7] At the request of the British government, the Liberal MP Sir William Beveridge drew up a report, published in 1942, which was to serve as the basis for building the social security system in Britain, but was also to inspire social security systems in all the developed countries. The principal is to ensure, in exchange for a contribution drawn directly from wages, a relief income in the event of “social risk” (sickness, accident, death, old age, unemployment, maternity, etc).

[8] It was also during World War II that the Dutch bourgeoisie planned, with the trade unions, a progressive increase in wages as a function of, though remaining lower than, the increase in productivity.

[9] CoC likes it when 2+2 makes 4; when they are told that subtracting 2 from 6 can also obtain 4, they find that this is contradictory. This is why CoC comes back to “the ICC and its contradictory considerations on armaments. While on the one hand armaments provided outlets for production to a point where for example the economic recovery after the crisis of 1929 was solely due to the arms economy, on the other we learn that arms production is not a solution to crises and that expenditure on armaments therefore represents an incredible waste for capital in developing the productive forces, that arms production should be put down on the negative side of the overall balance sheet” (CoC no. 22).

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace